Assess

| Site: | Learn: free, high quality, CPD for the veterinary profession |

| Course: | EBVM Learning |

| Book: | Assess |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 3 March 2026, 3:24 AM |

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. How can we assess implementation in practice?

- 3. Why do we need to assess?

- 4. Reflection as a quality improvement tool

- 5. Clinical audit as a quality improvement tool

- 6. Clinical audit in the veterinary world

- 6.1. Where to start in clinical audit

- 6.2. Making sure clinical audit gets done – the administrative side

- 6.3. Setting audit aims and objectives

- 6.4. Defining audit criteria/standards

- 6.5. Measuring performance – data collection and analysis

- 6.6. Drawing conclusions and making changes

- 6.7. Acting on the results of clinical audit – sustaining improvements

- 7. Beyond clinical audit - alternative ways to assess

- 8. Quiz

- 9. Summary

- 10. References

1. Introduction

Assess is the final step of the EBVM cycle, evaluating the implementation of evidence into clinical practice. This step assesses what, if any, impact there has been to patient care or healthcare provision as a result of evidence-based practice. EBVM starts in practice, as the questions should all come from those involved in providing veterinary care (Ask) and the Assess stage ensures EBVM stays in practice.

By the end of this section you will be able to:

- explain why it is important to assess/audit the implementation of EBVM in practice

- describe how to assess/audit EBVM in practice

- use practice examples to demonstrate the use of clinical audit and the assessment of EBVM in practice.

2. How can we assess implementation in practice?

As the final step of the EBVM cycle, Assess involves evaluation of evidence implementation into clinical practice to determine what, if any, impact on the quality of care has occurred as a result of evidence-based practice.

It is possible to assess implementation of EBVM through a number of formal and informal routes. For example, a formal evaluation of the process or outcomes of healthcare could be achieved through undertaking a clinical audit (see Assess 6).

An informal method of assessment could simply comprise personal reflection on individual cases at the end of a busy day. However, Assess also encompasses evaluation of, or reflection on, how the effectiveness and efficiency of any of the five steps in EBVM could be improved for addressing any future clinical questions. Personal reflection is discussed in more detail in Assess 4.

These assessments can be incorporated into small gaps of time throughout the day (for example, reflecting while having a cup of coffee, or mentally running through the day on your drive home), or specific times can be set aside to actively address individual questions or problems experienced in your daily practice, or by the business as a whole.

Various methods of approaching how you Assess the effect of applying EBVM to practice will be outlined in this section.

3. Why do we need to assess?

The only way we can establish whether patient care has improved through the application of evidence to practice is to measure the effect of the Apply stage.

EBVM is a tool to help us improve our clinical practice. To achieve this goal, we need to assess whether the process is helping us in our clinical decision-making in an effective manner. If a practice policy, diagnostic procedure or treatment strategy has changed as a result of finding (Acquire), appraising (Appraise) and applying (Apply) the evidence, it is important to look at the consequences of this change.

Questions to consider:

- How has it affected the patients?

- Did it make any difference?

- Has the quality of care improved or declined?

- Are further changes needed?

It is vital to assess what we do in order to ensure our practice is responding and adapting to the advances in the profession.

3.1 Benefits of assessing

Assessment of EBVM is evaluating the effectiveness of the EBVM process, or the impact of the implementation of new processes, guidelines or protocols, in clinical practice, for the benefit of veterinarians, clients and patients alike.

The benefits of reflecting on what we are doing and highlighting areas where we can make improvements are far reaching and can range from improved customer satisfaction and patient care, to improved biosecurity practices or financial returns.

The Assess step of EBVM allows us to assess and to uphold professional standards, and offers opportunities to improve the quality and effectiveness of the veterinary services we provide. Assessing also brings benefits beyond improving the quality of patient care including:

- developing a practice philosophy that supports EBVM

- identifying and promoting good practice

- helping to create a culture of quality improvement, within both the practice and the profession

- informing development of local clinical guidelines or protocols (Hewitt-Taylor, 2003)

- providing opportunities for education and training

- can help to identify requirements for further training/CPD (Moore and Klingborg, 2003)

- facilitating better use of practice resources

- helping to improve client communication

- building relationships between practice team members

- providing opportunities for increased job satisfaction

Another important outcome of assessment is the identification of areas where there are deficits in the evidence base, as well as the potential to identify actions we might undertake to help address those deficits.

3.2 Assess as part of clinical governance

A principal reason for assessing implementation of EBVM is as part of a clinical governance programme.

Clinical governance provides a comprehensive framework, including a number of different quality improvement systems (such as clinical audit, supporting and applying evidence-based practice, implementing clinical standards and guidelines, and workforce development) and promotes an integrated approach towards continuous quality improvement.

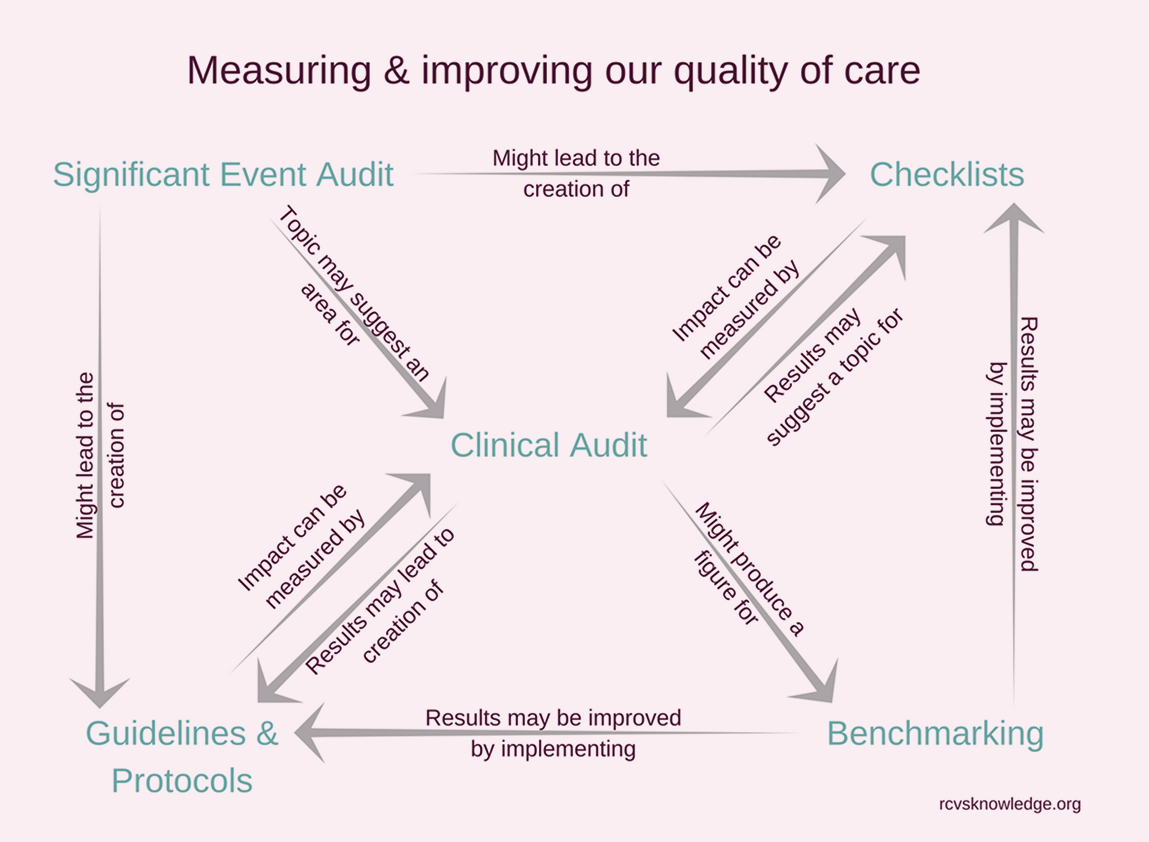

Figure 5: Measuring and improving our quality of care

For example, as can be seen in Figure 1 above, significant event audits might lead to the creation of checklists, guidelines and protocols, and the topic of a significant event audit may suggest an area for a clinical audit. The results of a clinical audit may lead to the creation of guidelines and protocols, and checklists, and the impact of these can also be measured by a clinical audit. A clinical audit might produce a figure for use in benchmarking. Benchmarking results might be improved by implementing guidelines and protocols, and checklists.

The RCVS Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Surgeons defines clinical governance as:

a continuing process of reflection, analysis and improvement in professional practice for the benefit of the animal patient and the client owner.

In the UK, the RCVS Practice Standards Scheme states that:

The practice must have a system in place for monitoring and discussing clinical cases, analysing and continually improving professional practice as a result.

and that:

Veterinary surgeons must ensure that clinical governance forms part of their professional activities.

Veterinary Hospitals in the UK must also comply with the following:

Regular morbidity and mortality meetings must be held to discuss the outcome of clinical cases. There are records of meetings and changes in procedures as a consequence.

and:

Clinical procedures carried out in the practice are audited and any changes implemented as a result.

But it’s not just abiding by professional standards that drives us to assess what we do. Development of an ethos of reflection on, and assessment of, our practices is a vital part of developing our confidence and competence as a veterinary professional.

4. Reflection as a quality improvement tool

At its simplest level, we can use reflection to assess clinical outcomes – either as an individual or as a group (for example, during clinical rounds).

We often only reflect on the cases where something went wrong or we had an unexpected outcome. However, any decision can benefit from reflection (Koshy et al., 2017) – whether it is implementation of a well-researched new treatment, diagnostic or biosecurity protocol or simply reflection on a series of cases that were managed in a particular way in order to better understand how that management might be improved. If we don’t reflect on what we are doing, our practices may remain stagnant and become rapidly outdated.

Reflection and unstructured EBVM is simple and easy to incorporate into everyday practice, but it is important to try to still follow the EBVM cycle. Reflection without support of the literature or without a clear question can lead to a vague outcome. Referring to the literature as part of your reflection allows you to utilise the entire EBVM cycle: Asking the correct question, Acquiring and Appraising the evidence, Applying that information and then finally Assessing if the application was appropriate. Reflecting about how you navigated the five stages of the EBVM cycle also offers a simple way of assessing your own performance as an EBVM practitioner.

While it may require some additional planning and time management compared to personal reflection, team-based reflection can be a very useful quality improvement tool (Shaw et al., 2012).

Example Scenario

Postoperative physiotherapy

During monthly clinical rounds in a busy small animal practice, Sam reported that his last case of cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) rupture had re-presented with rupture of the CCL in the contralateral limb three months after surgery.

On presentation, Sam had noticed that the dog was not using the limb he had initially operated on fully, and suspected poor return to function of the operated limb had been a contributing factor. The owner was upset because when she had anterior cruciate ligament surgery herself, she had received an intensive programme of physiotherapy postoperatively, and wondered if the lack of physiotherapy could have been a factor in her dog’s new CCL injury.

One of Sam’s colleagues, Nicky, could recall similar cases in the practice and remembered reading a paper about early intensive physiotherapy used postoperatively after CCL surgery in dogs. Sam and Nicky worked together in an informal EBVM cycle of reflection, asking the question ‘In dogs with CCL injury, does postoperative physiotherapy compared to our traditionally prescribed controlled exercise programme improve function in the operated limb?’.

They identified a small number of papers that supported this approach, and although the evidence was not based on large multicentre trials in dogs, they felt there was sufficient evidence to apply physiotherapy as part of the postoperative management plan.

Together they found a local animal-qualified physiotherapist and implemented a new practice guideline for referral of all CCL cases for postoperative physiotherapy, starting with Sam’s patient following its second surgery.

The head nurse was involved with keeping a record of the cases of contralateral limb CCL rupture, as well as documenting client feedback on the physiotherapy, all of which were scheduled to be reviewed in a meeting in 12 months’ time.

Key points:

- This example shows a simple use of EBVM to address a problem following reflection on a case (although it could equally have been used pro-actively before a problem arose).

- A question was asked, information was acquired and appraised (albeit relatively informally), and the veterinarians applied the information in developing a new management guideline for dogs with CCL injury.

- In order to ensure that this new management protocol is actually doing what the veterinarians hope it will do, it is essential that they also implement a system to assess the response against clear outcome measures. In this case the outcomes are:

- the number of cases presenting for contralateral limb CCL injury.

- client feedback on the postoperative management guideline.

- A realistic time frame was set in order to ensure the guideline could be appropriately evaluated.

5. Clinical audit as a quality improvement tool

Clinical audit can help with assessing the implementation of EBVM in practice, for personal and practice-level professional improvement.

Clinical audit is:

a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes through systematic review of care against explicit measures and the implementation of change. (NICE, 2002)

Brief introductions to key elements of the stages of the clinical audit cycle are outlined in this chapter. For a more comprehensive overview, RCVS Knowledge has collated a wide range of quality improvement resources , including an e-learning course on clinical audit and a short summary infographic about the stages of clinical audit .

The key components of clinical audit are:

- measurement (measuring a specific element of clinical practice)

- comparison (comparing results with the recognised standard)

- evaluation (reflecting on the outcome of an audit and where indicated, changing practice accordingly).

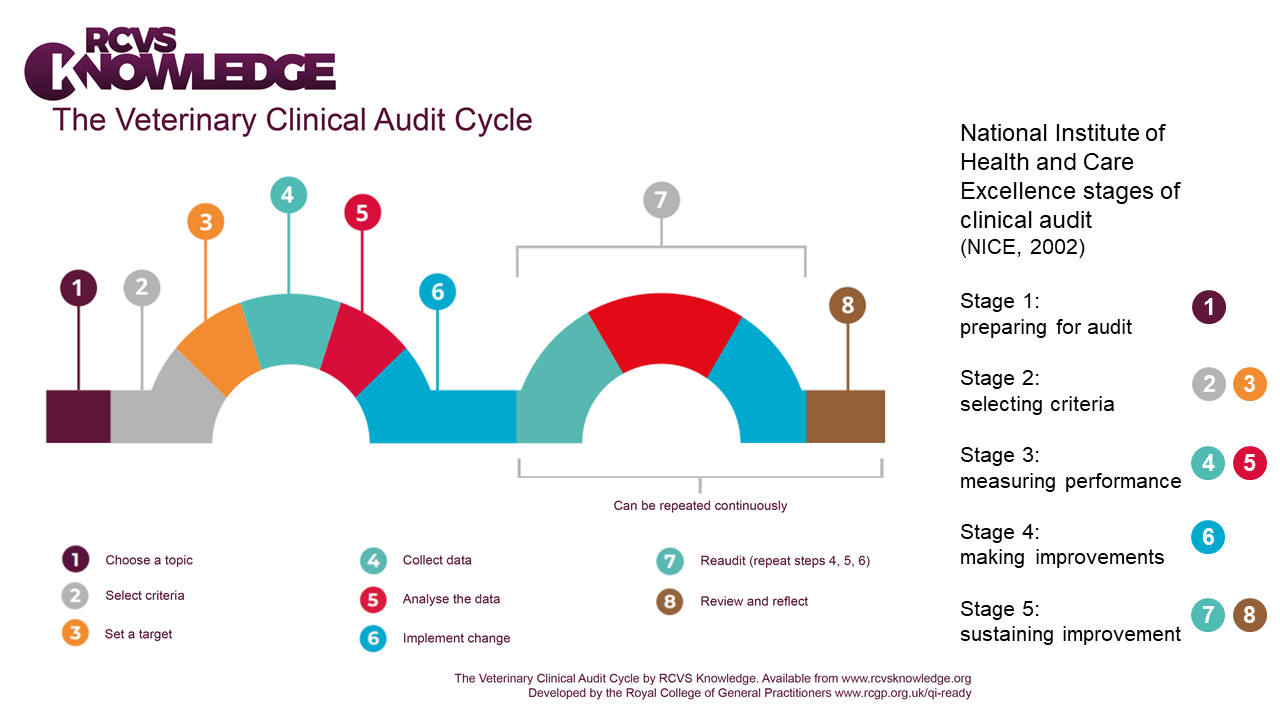

Figure 6 below shows the eight-stage clinical audit cycle from RCVS Knowledge , together with how these stages align with the commonly-used five-stage audit cycle defined by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2002).

Figure 6: The veterinary clinical audit cycle

The eight stages in the veterinary clinical audit cycle are listed in Figure 6 above, alongside related stages in the NICE five-stage audit cycle:

- Choose a topic (Stage 1 of NICE audit cycle 'Preparing for audit')

- Select criteria

- Set a target (Stages 2 and 3 relate to Stage 2 of NICE audit cycle 'Selecting criteria')

- Collect data

- Analyse the data (Stages 4 and 5 relate to Stage 3 of NICE audit cycle 'Measuring performance')

- Implement change (Stage 4 of NICE audit cycle 'Making improvements')

- Reaudit (repeat steps 4, 5 and 6)

- Review and reflect (Stages 7 and 8 relate to Stage 5 of NICE audit cycle 'Sustaining improvement')

Audit and research are different, although there can be overlap, and audits have potential to identify where further research is needed.

Research is concerned with discovering the right thing to do whereas audit is intended to make sure that the thing is done right. (Smith, 1992)

Other articles on clinical audit including some comparisons with research include: Viner (2009); Wylie (2015); Waine & Brennan (2015) and Waine et al. (2018a, 2018b).

6. Clinical audit in the veterinary world

Clinical audit is a well-established and widely used quality improvement tool in human health care, and there is a huge wealth of available resources regarding audit methodology, which can readily be adapted for use in veterinary settings. However, there are some key differences we should consider when embarking on a veterinary clinical audit.

Criteria-based (or standards-based) audits are the most common type of clinical audit undertaken in human health care, where high quality clinical guidelines are the preferred source for deriving audit criteria from evidence (NICE, 2002). One thing to be very careful about in comparing the audit process in veterinary medicine to the audit process in human medicine, is that there are many fewer clinical guidelines available in veterinary medicine . Therefore, in many situations, we need to rely on developing our own evidence-based criteria (Mair, 2006) .

Another key difference in human health care is the provision of protected time allocated for doctors to undertake medical audit activities (National Health Service (NHS) White Paper Working for Patients, 1989). This may not be feasible within a busy veterinary practice setting, and therefore careful planning is required to ensure completion of a successful audit project, including particular attention to selecting the right audit team, setting clear and achievable audit objectives and methods for data collection. All these considerations are discussed more fully on the following pages.

As well as the quality of care we provide for our patients, we must also recognise the importance of animal owners as veterinary service users. In addition to patient-centred outcomes, veterinary clinical audit can be used to evaluate the care delivered from the client’s perspective, for example through assessing client satisfaction with a new treatment or procedure.

Like most things in life, clinical audit is best learnt through practical experience. It is better to gain this experience with small, simple projects that are narrowly focused rather than attempting to do everything all at once.

Choosing an area to audit

The overarching aim of clinical audit is to improve the quality of care, therefore try to choose an audit topic that offers realistic potential to lead to measurable improvements for patients, clients or the practice team.

Start with something that:

- occurs relatively frequently, or is of significance when it does occur

- has a clearly defined outcome or is clearly measurable

- is a priority or a topical issue for you or your practice

- you care about (or believe that some stakeholders care about)

- is in an area in which change is possible, should findings of the audit identify that some improvement is required

Good areas for a first audit are:

- re-audit of a clinical audit topic previously carried out by colleagues/peers

- suspected nosocomial infections

- compliance with a protocol or guideline

- peri-operative deaths

- postoperative complications for common elective surgeries (e.g. neutering ).

Types of clinical audit

Criteria-based (or standards-based) Click to expand

This is a clinical audit which seeks to improve services through comparing current practice against a standard that has already been set by examining:

- whether or not what ought to be happening is happening

- whether current practice meets required standards

- whether current practice follows published guidelines

- whether clinical practice is applying the knowledge that has been gained through research

- whether current evidence is being applied in a given situation.

Significant event audit Click to expand

Significant event audit (Mosedale, 2017) is defined as:

an event thought by anyone in the team to be significant in the care of patients or the conduct of the practice (Pringle et al.,1995)

Responding appropriately to findings from incidents, errors and near misses is an essential element of quality improvement.

What can be audited?

Any aspect of the structure, process or outcome of health care can be evaluated in a clinical audit (NICE, 2002).

Structure audit Click to expand

- related to the organisation or provision of services

- staff and resources that enable healthcare

- environment in which care is delivered

- facilities/equipment

- documentation of policies/procedures/protocols

Practical examples of structure audits

Structure audits evaluate environmental factors within which health care is delivered, and can provide an indirect assessment of a patient’s care. An example of a structure audit is auditing whether the right equipment and team members are available when planning a new procedure in the practice (for instance, a laparoscopic spay). A structure audit for an ambulatory practice could be auditing which equipment is carried in different vets' cars.

Process audit Click to expand

- related to procedures and practices implemented by staff in the prescription, delivery and evaluation of care

- diagnostic investigations, treatments, procedures

- may be specific to the clinical process or to service/administrative processes

Practical examples of process audits

Process measures may include communication, assessment, education, investigations, prescribing, surgical or medical interventions, evaluation, and documentation (NICE, 2002). Process audits provide a more direct measure of the quality of care, and examples include: appropriate prescribing of fluoroquinolones (Dunn and Dunn, 2012), evaluating the number of equine laminitis cases that undergo laboratory testing for an underlying endocrine disorder, or assessing practice processes for patient discharge following hospitalisation.

Outcome audit Click to expand

- related to any outcome following delivery of care (i.e. not solely limited to patient outcomes)

- physical or behavioural response to an intervention

- measurable change in health or survival status

- outcome measures can be:

- desirable e.g. improvement in the patient’s condition or quality of life

- undesirable e.g. adverse effects of a treatment

- measuring the views of those who use services (e.g. level of knowledge or satisfaction) enables assessment of the care delivered from the client’s perspective e.g. client satisfaction

Practical examples of outcome audits

Outcomes are not a direct measure of the care provided, and not all patients who experience substandard care will have a poor outcome; however outcome audits are the most frequently performed type of audit in veterinary medicine (Rose et al., 2016a). Examples of outcome audits include evaluation of postoperative complications following tibial tuberosity advancement surgery (Proot and Corr, 2013), evaluation of canine quality of life following medical treatment of osteoarthritis, reduction in adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in horses diagnosed with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) following treatment with pergolide, or evaluating client satisfaction with the practice’s new weight management clinic for obese dogs.

Example Scenario

Small animal dental imaging

Tom has just recently performed a Knowledge Summary for his practice, which demonstrated that high definition computed radiography in dogs and cats has superior diagnostic capability for periodontal disease compared to visual examination.

On the basis of this evidence, and because of the potential to improve animal welfare by reducing additional visits or prolonged morbidity associated with undiagnosed disease, the partners have just invested in dental radiography. In accordance with available dental care guidelines (Bellows et al., 2019), Tom’s practice recommended survey intraoral radiographs for all dogs and cats presented for dental treatment, with subsequent extraction of any diseased teeth identified.

Tom now wants to establish and demonstrate to the partners (practice owners) that this has been a good investment and that it has improved animal welfare. A practice meeting is held to discuss how best to assess their new radiography system. The partners are keen to discover the cost-effectiveness of their equipment purchase, but everyone agrees that client feedback would be a useful measure of clinical benefit. Therefore, Tom plans an outcome clinical audit, evaluating owner-reported improvement in health-related quality of life following dental treatment.

Key points:

This is an example of an outcome audit, using client feedback to evaluate the quality of care following practice investment in new equipment for dental radiography.

Tom selected his audit topic as it was an important area for his practice, and of considerable interest to him personally.

6.2 Making sure clinical audit gets done – the administrative side

A clinical audit team should include representatives from all groups involved in delivering veterinary care. All members of a practice team can lead or make a valuable contribution to audits, depending on the area being audited.

The auditing process is not a light undertaking, and lack of time and resources are frequently reported as the main barriers to undertaking clinical audit in human medicine. Administrative colleagues in a practice team are a source of valuable knowledge and expertise, as they have extensive experience that can be used to help smooth the process and make sure all the practicalities of the audit have been addressed.

Specific points to be addressed include:

- Are there any team members with previous experience of clinical audit available to help with training colleagues?

- Who within the practice will be responsible for collecting the data?

- Are the data required for the audit collected routinely in electronic clinical records, case notes or databases?

- Does an appropriate recording system exist in the practice (e.g. is a paper-based system most appropriate? How feasible is extracting the required data from the current practice computer-based system?)

- Who will analyse the audit data?

- Are the data collected for the audit fit for purpose?

- With what will you compare the results you generate?

- How will you disseminate the results, both within and outside the practice?

6.3 Setting audit aims and objectives

A clinical audit with no clear purpose will deliver little or no improvement to the quality and effectiveness of clinical care. Clearly stated aims and objectives specify the purpose and scope of the audit, and provide a basis for keeping the audit focused.

Remember the primary goal of clinical audit is quality improvement, so this should be reflected in your audit aims.

Aims are broad, simple statements that describe what you want to achieve.

Ideally, audit aims should include verbs such as: improve, increase, enhance, ensure or change (Buttery, 1998), which convey the intention to measure current practice and identify where improvement may be needed.

Practical example Click to expand

An audit of surgical safety checklists might have as its overall aim: ‘To improve adherence with completion of surgical safety checklists for all surgical procedures performed under general anaesthesia’

Audit objectives are more detailed statements that are used to describe the different aspects of quality which will be measured to show how the aim of the clinical audit will be met.

Therefore audit objectives should contain a verb to describe what you want to do, the intervention or service you are evaluating and an aspect of quality related to that intervention or service (Maxwell, 1992 ).

Practical example Click to expand

An audit of surgical safety checklists might have specific objectives: ‘To increase the number of surgical cases for which a completed surgical safety checklist is included within the patient’s clinical records’ and ‘To ensure the content of the surgical safety checklist provides an accurate record of pre-induction, intra-operative and post-surgical checks carried out’

Example Scenario

Completion of financial consent forms

At Matthew’s veterinary hospital, owners are required to complete two consent forms: one for the treatment/procedure and one that records any estimate provided and obtains financial consent for the procedures to be performed. After a client complaint regarding the cost of treatment, the administrative members of the team report that the financial consent form had not been completed at the time of admission for this case.

Matthew plans a process clinical audit, to quantify and improve the rate of consent form completion at his hospital.

His audit aim is “to improve the completion rate of financial consent forms for patients admitted to the hospital”.

He sets specific objectives: “to ensure all consent forms are filled in at admission by reception team members or clinicians with a procedure and financial estimate” and “to ensure all financial consent forms are signed by owners to serve as a written record of them having provided informed consent and agreeance to the financial estimate provided”.

6.4 Defining audit criteria/standards

The terms ‘criteria’ and ‘standards’ often lead to confusion as these terms have been used differently by various professional groups and writers across healthcare, and are frequently used interchangeably.

Audit criteria are clearly defined, measurable, explicit statements, which are used to assess the quality of care.

For criteria to be valid and lead to improvements in care, they need to be:

- evidence-based

- related to important aspects of care

- measurable (NICE, 2002)

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence recommends using high quality clinical practice guidelines to develop audit criteria (NICE, 2002). There are several different appraisal tools available to help you evaluate the quality of clinical guidelines (for example, the AGREE II checklist developed by the AGREE Collaboration; see also Siering et al., 2013). These appraisal tools can be utilised to determine whether or not guidelines represent a suitable source for deriving your audit criteria. However, published clinical guidelines are scarce in veterinary medicine, with professional consensus statements offering the closest available option in many cases.

If clinical guidelines or up-to-date systematic reviews are not available, a literature review may be carried out to identify (Acquire) the best (Appraise) and most up-to-date evidence from which audit criteria may be generated.

You may already have evidence-based clinical protocols or guidelines for your practice, which you can use to define ‘local’ audit criteria. Where there are no known or available criteria, one other option is to compare your audit data to historical clinical records over time.

Each audit criterion should have a performance level or target assigned to it (usually expressed as a percentage). Again, some overlap and confusion exists between different publications and guidance about clinical audit – some sources use the term ‘standard’ to define the performance level or target for expected compliance.

Practical examples Click to expand

A structure audit evaluating practice waiting times:

|

Criterion |

Target/performance level |

|

All patients should be seen within 15 minutes of appointment time |

90% |

A process audit of equine laminitis:

|

Criterion |

Target/performance level |

|

All equids diagnosed with acute laminitis, with no clinical signs of systemic illness (such as systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)), should receive a follow-up appointment for endocrine laboratory testing |

100% |

An outcome audit of perioperative hypothermia management:

|

Criterion |

Target/performance level |

|

All dogs with postoperative hypothermia should have rectal temperature measured hourly during recovery until a temperature of ≥37·5°C is reached (adapted from Rose et al., 2016b) |

100% |

In many cases, we would aim to achieve 100% compliance with our evidence-based ‘best practice’, as set out by our audit criteria. However in practice, performance levels are a compromise between clinical importance, practicability and acceptability and for various reasons, it may not always be possible to meet 100% compliance.

Where you have set your target performance level based on published literature, you should note that levels of performance achieved in trials or research studies are helpful, but they often include very well defined study populations and should not be regarded as uniformly achievable in unselected patient populations in a practice setting. Clinical practice benchmarking can also be used to set and maintain target levels of performance.

There may be justifiable reasons why some cases might not comply with a specific audit criterion, and these cases should not be included in your audit data analysis. These exceptions should be defined along with your audit criteria, prior to data collection.

Example Scenario

Small animal dental imaging

Although published practice guidelines emphasise the importance of dental health in canine and feline quality of life (Bellows et al., 2019), Tom was unable to identify evidence to help him set the criteria and target performance level for his audit. The practice team agree on a criterion of owner-reported improvement following dental treatment. Tom found a systematic review of oral health-related quality of life following dental treatment under general anaesthesia in children (Knapp et al., 2017). Considering this to be a useful proxy for owner assessment of quality of life in his patients, Tom uses data from studies included in this review for his audit. Tom sets a target performance level of 65% of dental cases being reported to have improved quality of life following treatment, based on 63% of children having met or exceeded a minimal clinically important difference in quality of life following dental treatment (Knapp et al., 2017).

Key point:

In the absence of species-specific evidence to set his target performance level, Tom utilised comparative information from a systematic review of a similar area in human medicine.

Example Scenario

Completion of financial consent forms

The criteria for Matthew’s audit were defined by local consensus as:

1) the percentage of financial consent forms with the estimate filled in

2) the percentage of financial consent forms with the owner or owner representative’s signature

Key point:

Matthew’s audit team agree that the target performance level for each process criterion should be set at 100% based on guidance provided by the RCVS that informed consent and documentation of consent is essential. The team agreed that emergency cases brought in by a transporter only, with no owner or representative present, would be excluded from the clinical audit (exceptions to the audit criteria).

6.5 Measuring performance – data collection and analysis

EBVM includes patient, client, experiential and practice factors as well as the peer-reviewed scientific literature, and all of these will influence the information you gain and want to gain from a clinical audit.

For example, you might want to know if implementation of a protocol or new treatment has improved client satisfaction, decreased costs to the client, increased profit margins, saved time, improved veterinary compliance, reduced side effects, increased survival, or increased quality of life. In order to answer this ‘What if?’, you need to ensure you are asking the right questions to the right person (e.g. quality of life is often best evaluated by owners through practical questions involving the animal’s daily life, not by their veterinarian).

Your audit aims and objectives should be the primary consideration when deciding which data you will need to collect for your audit. You should only collect data required to show whether or not performance levels have been met for each criterion – collecting additional data provides little or no benefit, and is more time consuming.

When planning data collection for your audit, there are several aspects you should consider in advance, including:

- what data collection strategy is most likely to result in complete and reliable data?

- audit population

- what inclusion or exclusion criteria would you use to identify suitable cases for the audit?

- how many cases will you need to include?

- over what time period would you need to collect data?

- will you collect prospective or retrospective data?

- what data source(s) will you use?

- is all the information you require routinely recorded on electronic clinical records?

- will you need to design a data collection tool? (example in Waine et al. 2018b)

Example Scenario:

Small animal dental imaging

Tom’s audit sample includes all dogs and cats receiving dentals within the 12 months following installation of the computed radiography system. Tom extracted the total cost per dental visit from clinical records. His trainee vet nurse has designed an owner feedback questionnaire (including key questions about overall demeanour, eating behaviour and halitosis, and quality of life) as part of her nursing degree course.

Key point:

The audit team included the veterinary nurse, making use of her expertise to design and administer the owner questionnaire for audit data collection.

The first step is often to develop ways to obtain data that will help you assess what you are doing in your practice, so don’t worry if the first attempt at data collection isn’t successful. If you discover you need more data, try to implement changes that will make things better on the next attempt.

Data collection is only part of the process of measuring performance, and once you have collected your audit data, you need to determine what data analyses to undertake. Remember that the focus of data analysis for clinical audit is to convert a collection of data into useful information in order to identify the level of compliance with your agreed target/performance level. A common pitfall is the temptation to over-analyse or over-interpret the data that are obtained. Data analysis should be kept as simple as possible – if you are using hypothesis tests or advanced statistical methods, you are very likely to be answering a research question, not undertaking a clinical audit.

Most audits will involve calculating some basic summary/descriptive statistics (such as means or medians, and percentages). Simply calculating the percentage of your audit cases that complied with your criteria will allow you to decide if your results show that the changes you have made are as good as, or better than, your defined target performance level(s).

Some examples of ways in which we could monitor changes against criteria might be:

- Making sure that recurrence or complication rates for a specific disorder are equivalent to a recent multicentre case series found in the literature.

- Setting nosocomial infection rates to reduce by a certain percentage from the current baseline if no history of actual rates is available.

- Insisting that client-reported quality of life or pain score ratings should be equivalent to published results, should improve from what they currently are in your clinic, or should be greater than a predefined percentage.

- Necessitating that client satisfaction should improve, or remain static where it has already been at high levels.

- Requiring veterinary or owner compliance to be above a certain cut-off percentage (e.g. veterinary adherence to safety protocols would be expected to be 100%, while expectations of client compliance to puppy vaccination schedules may be set slightly lower).

- Stipulating that cost implications of implementing a new protocol should be comparable to those associated with the previous protocol, or that the new protocol will have a demonstrable cost benefit to the client and/or practice.

Example Scenario:

Small animal dental imaging

Over the year following implementation of dental radiography, there was a 20% increase in total extractions, which was consistent with radiography identifying additional diseased teeth in dogs and cats. The average dental invoice increased by 36%, providing a noticeable increase in gross income. No client queried the bill (although a practice policy of providing clear estimates for dental work had been instituted concurrently).

During the period of the audit there were 95 responses to the animal welfare questionnaire: 60 from dog owners and 35 from cat owners. 85% of dog owners indicated a positive response, with dogs showing increased activity levels (‘acting years younger’) and/or owners reporting reduced halitosis. Only 60% of cat owners indicated a positive response, with changes mentioned primarily associated with improved appetite. There were no reports of deterioration in health or quality of life, however the remaining 40% of respondents that indicated that they did not notice any particular response to dental treatment in their pets. Overall, 76% of owners reported significant improvement in their animal’s wellbeing following dental treatment; however, owner-reported outcome for cats fell just below Tom’s target performance level of 65%.

Key point:

Data analysis for Tom’s clinical audit required simple calculation of the percentage of dental cases meeting the audit criterion of improved owner-reported health-related quality of life following treatment.

6.6 Drawing conclusions and making changes

Once you have the results, it is time to act on them! If you started off by establishing criteria by which you will assess your current practice, then it is a simple matter of comparing your results with those criteria, and reporting your results to the practice team.

In many cases, the audit process may well indicate that no change is required. For example, an audit of peri-operative fatalities, or post-surgical wound breakdowns/infections, may indicate that rates have not changed recently and that they remain at levels that are similar to those in other clinics. The point of clinical audit is that it provides baseline data or reference points for comparison. Clinical audit also ensures that a process is in place that will likely result in early identification if things start to go wrong.

Alternatively, your data analysis and interpretation might identify some clinical areas that should be addressed (e.g. areas for improvements in care/performance/service provision etc.). You should use your findings to inform ways of improving, which should be the basis of the recommendations of your audit. These recommendations can be used to develop a realistic and achievable action plan, specifying what needs to be done, how it will be done, who is going to do it and by when. Implementing changes that will improve areas of poorer performance is often the hardest part of any audit.

Example Scenario:

Small animal dental imaging

The implementation of dental radiography was considered beneficial from both an animal welfare and financial aspect, and client feedback was good, despite the increased cost. As the proportion of cats with an owner-reported improvement was lower than desired, Tom’s practice decided to utilise the dental guidelines to implement a new practice protocol for discharge appointments for feline patients after dental treatment, where the vet or head nurse would show owners their cat’s dental chart and radiographs, and a follow-up appointment in 10–14 days would be booked. The practice also decided to continue to monitor client feedback, dental invoices and the numbers of extractions they perform, with a view to reviewing the data again in 12 months’ time.

Key point:

A realistic time frame was set for re-audit in order to ensure the changes implemented to improve outcomes in feline patients could be appropriately evaluated.

Example Scenario:

Completion of financial consent forms

Matthew collected audit data for the previous 100 consecutive hospital admissions, and found that while treatment/procedure consent forms were completed for 99% of cases, completion rates for financial consent forms were considerably lower. Only 57% of financial consent forms included a written estimate and 56% were signed by the owner or representative.

Further analysis shows that financial consent forms were completed for 95% of cases admitted out-of-hours, but for only 46% of cases admitted during normal working hours. He identified that completion of consent forms for out-patient cases was lower than for in-patient cases. Matthew used process mapping as part of his root cause analysis to develop an understanding of the reasons why the performance level for completion of financial consent forms was not being reached. This involves mapping out each step of a process in sequence so that areas for improvement can be identified. As a result of this, the audit team determined that the time of admission would be the easiest point to obtain financial consent, and that vets were best suited to discuss financial estimates and consent with clients. Matthew recognised that a better understanding of the consent process from an owner’s perspective could help to inform future improvements (Whiting et al., 2017).

Matthew presented his audit findings at a hospital team meeting, including his recommendation that a change of policy should be implemented, where the vet admitting the patient would be responsible for discussing financial costs and obtaining financial consent from the client. Matthew plans to re-audit in six months, including collecting data regarding owners’ opinions of the consent process.

6.7 Acting on the results of clinical audit – sustaining improvements

As we become more proactive in EBVM, we may go further than identifying areas requiring improvement and be able to proactively establish a system to regularly (continuously or periodically) assess outcomes. We can then use that information to review our treatments, protocols and procedures, for the betterment of ourselves and our veterinary patients.

The overarching principle to successful implementation and adoption of both EBVM and clinical audit is to keep things small and simple, especially to start off with. It should be possible for you to set a modest goal of clear benefit, and to achieve it. Communication is also important – be sure you keep records of the process and of your findings so that you can compare the next cycle with the last. Discuss the tasks and progress with colleagues both during and after each audit cycle. Good communication will help to involve the more experienced (and often busiest) members of the practice who may at first be reluctant or unable to engage otherwise.

While the primary goal of clinical audit is improving performance, sustaining that improvement is also essential. The audit cycle is a continuous process, and requires re-auditing to ‘close the loop’. Re-audit is central to both assessing and maintaining the improvements made during clinical audit. The same methods for sample selection, data collection and analysis should be used to ensure that the data are valid and comparable with the results from previous audit(s).

Part of the audit process should be for you and your colleagues to identify thresholds that might trigger you to further action. That action might involve further in-depth investigation, or it may involve an increased frequency of the audit cycle to see if preliminary results are indeed a trend in the wrong direction, or just an anomaly that should be monitored but perhaps not acted on at this time. On the whole, a common sense approach is required. However, an explicit and systematic process can help veterinary practices avoid falling into complacency or inertia.

Where an initial audit demonstrates that desired performance levels are not being reached and an action plan has been put in place, the audit should then be repeated to show whether the changes implemented have improved care or whether further changes are required. This cycle is repeated until the desired standards are being achieved. Where the initial audit showed that no changes or improvements were required, re-auditing allows you to ensure that the high standards of care are being maintained.

Sustainable improvements in quality of care are going to be more readily achieved where everyone in the practice (or profession) is aware, and supportive, of planned audit activity. In addition to fostering a culture of continuous improvement, longer term success may require practice development; for example, there may be a requirement for training or organisational changes, such as modifying format, content or quality of clinical records, updating or changing practice management software or time allocation for team members involved in clinical audit to gather and analyse.

The reading material in the next section 'Beyond clinical audit – alternative ways to assess' is additional. You might find it useful to deepen your understanding.

7. Beyond clinical audit – alternative ways to assess

While clinical audit remains the most widely used methodology in human health care, there are a number of other quality improvement tools that you can use to assess.

Traditional clinical audit is a formal way to find out if the care we are providing is in line with recognised standards, but there are a large number of other quality improvement tools that you can use to Assess (Hughes, 2008). Examples of some of these alternative methods are outlined below.

Plan-do-study-act Click to expand

Plan-do-study-act (PDSA) methodology (Taylor et al., 2013) is a simple form of cyclical assessment of practice, which can be used to drive small steps of change in practice at a local level. The PDSA is a small, rapid cycle designed to test, measure impact and test again. It allows users to design the process so that it makes their life easier, while retaining the quality improvement effect.

Plan: identify a change aimed at improving quality of care and develop a plan to test the change

Do: test the effect of this change

Study: observe, analyse and learn from the test to evaluate the success of the change, or identify anything that went wrong

Act: adopt the change if it was entirely successful, or identify any modifications required to inform a new PDSA cycle

Clinical Scenario

Small animal resuscitation

Bella, an 8-month-old lurcher, had fracture fixation surgery but she did not regain normal limb function and follow-up radiographs showed non-union, therefore amputation of the limb was determined to be the best treatment option. During limb amputation surgery, Bella went in to cardiopulmonary arrest. Unfortunately, the locum nurse struggled to find the drugs required by the anaesthetist for advanced life support, and Bella died despite cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Head nurse Lynne realises that implementing resuscitation training for all staff could help reduce the risk of this happening in the future (PLAN). Lynne reviews available guidelines (Fletcher et al., 2012) and together with the anaesthetist, she prepares a short lecture regarding CPR to provide in-house training for all nursing staff. She also organises an induction for all new staff, to ensure that they know the location of the resuscitation trolley in theatre, and that they are familiar with the layout and contents of the resuscitation trolley (DO). Lynne informally assesses the benefit of her training and induction by setting a basic quiz for nursing staff to take afterwards. The training is well received and the nurses perform well in the quiz, however since cardiopulmonary arrest thankfully happens very rarely in their practice, some of the nurses are concerned that they may not remember everything they have learned in the future. They also highlight that for some surgeries, interns are more frequently involved in assisting the anaesthetist than nurses (STUDY). Lynne realises that all clinical staff in the practice (vets, nurses and veterinary care assistants) should receive the CPR training and resuscitation trolley induction, and that including some practical skills training should improve learning and knowledge retention. She also devised a more structured assessment for staff after CPR training, and creates an emergency drug list with a dosing chart, which is kept with the drugs in the resuscitation trolley (ACT).

Lynne plans to provide refresher training to all staff every six months, based on available guidelines (Fletcher et al., 2012). She aims to repeat the PDSA cycle following implementation of her new training methods, using staff feedback and post-training assessment to test what works well and to learn from what does not work. This will also allow her to determine whether her training process is reliable, and that it works for different staff teams.

Key points:

For a rare outcome like cardiopulmonary arrest, assessing the impact of CPR training via clinical audit would have required a very long audit time frame – the PDSA cycle allowed Lynne to assess her intervention in a much shorter period.

Run charts Click to expand

A run chart is a graph of data over time, and offers a simple and effective tool to help you determine whether the changes you are making are leading to improvement. Run charts are simple to construct – the horizontal (x) axis is usually a time scale (e.g. weeks; April, May, June, etc.; or quarter 1, quarter 2, etc.) and the vertical (y) axis is the aspect of health care being assessed (e.g. surgical site infection rate, daily magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) start time, compliance with completion of surgical safety check lists).

Once you have at least ten observations, you can plot your data and calculate the median value, which is then projected into the future on the chart. Annotate your run chart to indicate where any changes were implemented. There are simple rules to help you interpret your run chart and to determine if a change has resulted in an improvement (Perla et al., 2011).

Run charts can be a helpful way to make progress visible to the practice team, providing a powerful display of the linkage between change and improved outcomes, and to ensure that improvement is being sustained over time.

Performance polygons Click to expand

Performance polygons offer a method to allow you to Assess multiple different aspects of quality of care in a single visual representation. Each outcome measure is plotted on a single line from ‘lowest performance’ to ‘best performance’ and performance data are then plotted, with the lines for each measure joined to form a ‘performance polygon’ (Cook et al., 2012). Markers can be used to show benchmark data or results of previous audit or assessments, to facilitate comparisons of overall performance. This could offer a simple method for you to track your own clinical or EBVM performance over time.

Health failure modes and effects analysis Click to expand

Health failure modes and effects analysis (HFMEA) is a systematic, proactive quality improvement method for process evaluation. It is a particularly useful method for evaluating a new process prior to implementation or for assessing the impact of a proposed change to an existing process.

A multidisciplinary team representing all areas of the process being evaluated identifies where and how a process might fail (failure modes), possible reasons for failing (failure causes) and assesses the relative impact of different failures (failure effects). Failure mode causes are prioritised by risk grading (hazard analysis) to identify elements of the process in most need of change (Marquet et al., 2012). Team members with appropriate expertise then work together to devise improvements to prevent those failures.

8. Quiz

9. Summary

Learning outcomes:

You should now be more familiar with how to:

- explain why it is important to assess/audit the implementation of EBVM in practice

- describe how to assess/audit EBVM in practice

- use practice examples to demonstrate the use of clinical audit and the assessment of EBVM in practice.

10. References

Bellows, J. et al. (2019) 2019 AAHA Dental Care Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. Journal

of the American Animal Hospital Association, 55 (2), pp. 49-69

Buttery, Y. (1998) Implementing evidence through clinical audit. In: Bury, T. and Mead, J. (eds) Evidence-based Healthcare: a Practical Guide for Therapists. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 182-207

Cook, T. M., Coupe, M. and Ku, T. (2012) Shaping quality: the use of performance polygons for multidimensional presentation and interpretation of qualitative performance data. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 108 (6), pp. 953-960

Dunn, F. and Dunn, J. (2012) Clinical audit: application in small animal practice. In Practice, 34 (4), pp. 243-245

Fletcher, D.J. et al. (2012) RECOVER evidence and knowledge gap analysis on veterinary CPR. Part 7: Clinical guidelines. Journal of

Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care, 22 (s1), pp. S102-S131

Hewitt-Taylor, J. (2003) Developing and using clinical guidelines. Nursing Standard, 18 (5) , pp. 41-4

Hewitt-Taylor, J. (2004) Clinical guidelines and care protocols.

Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 20 (1), pp. 45-52

Koshy, K. et al. (2017) Reflective practice in health care and how to reflect effectively. International Journal of Surgery Oncology, 2 (6), e20

Knapp, R. et al. (2017) Change in children's oral health‐related quality of life following dental treatment under general anaesthesia for the management of dental caries: a systematic review. International

Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 27 (4), pp. 302-312

Mair, T.S. (2006) Evidence-based medicine and clinical audit: what progress in equine practice? Equine

Veterinary Education, 18 (1), pp. 2-4

Marquet, K. et al. (2012) ENT One Day Surgery: critical analysis with the HFMEA method. B-ENT, 9, pp. 193-200

Maxwell, R.J. (1992) Dimensions of quality revisited: from thought to action. Quality in Health Care, 1 (3), pp. 171

Moore, D.A. and Klingborg, D.J. (2003) Using clinical audits to identify practitioner learning needs. Journal

of Veterinary Medical Education, 30 (1), pp. 57-61

Mosedale, P. (2017) Learning from mistakes: the use of significant event audit in veterinary practice. Companion Animal, 22 (3), pp. 140-143

Mosedale, P. (2019) Clinical audit in veterinary practice the role of the veterinary nurse. The Veterinary Nurse, 10 (1) , pp. 4-10

Mosedale, P. (2020) Quality improvement, checklists and systems of work: why do we need them? The Veterinary Nurse, 11 (6) , pp. 244-249

National Health Service (NHS) White Paper: Secretaries of State for Health, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland (1989) Working for patients. London: HMSO (Cmnd 555)

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2002) Principles of best practice in clinical audit. Radcliffe Medical Press: Abingdon. Available from: Principles-for-best-practice-in-clinical-audit.pdf [

Perla, R.J., Provost, L.P. and Murray, S.K. (2011) The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning from variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Quality & Safety, 20 (1), pp. 46-51

Pringle, M. et al. (1995) Significant event auditing. A study of the feasibility and potential of case-based auditing in primary medical care. Occasional paper (Royal College of General Practitioners), (70), i.

Proot, J.L.J. and Corr, S.A. (2013) Clinical audit for the tibial tuberosity advancement procedure. Veterinary

and Comparative Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 26 (4), pp. 280-284

Rose, N., Toews, L. and Pang, D.S. (2016a) A systematic review of clinical audit in companion animal veterinary medicine. BMC Veterinary Research, 12 (1), p. 40

Rose, N., Kwong, G.P. and Pang, D.S. (2016b) A clinical audit cycle of post‐operative hypothermia in dogs. Journal of Small

Animal Practice, 57 (9), pp. 447-452

Shaw, E.K. et al. (2012) How team-based reflection affects quality improvement implementation: a qualitative study. Quality

Management in Health Care, 21 (2), pp. 104

Siering, U. et al. (2013) Appraisal tools for clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. PLoS One, 8 (12), e82915

Smith, R. (1992) Audit and research. BMJ, 305 (6859), pp. 905

Taylor, M. (2013) Systematic review of the

application of the plan–do–study–act method to et al improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Quality &

Safety, 23 (4), pp. 290–298

Viner, B. (2009) Using audit to improve clinical effectiveness. In Practice, 31 (5), pp. 240-243

Waine, K. and Brennan, M. (2015) Clinical audit in veterinary practice: theory v reality. In Practice, 37 (10), pp. 545-549

Waine, K. et al. (2018a) Clinical audit in farm animal veterinary practice. In Practice, 40 (8), pp. 360-364

Waine, K. et al. (2018b) Clinical audit in farm animal veterinary practice. Part 2: conducting the audit. In Practice, 40 (10), pp. 465-469

Whiting, M. et al. (2017) Survey of veterinary clients’ perceptions of informed consent at a referral hospital. Veterinary Record, 180 (1), pp. 20

Wylie, C.E. (2015) Prospective, retrospective or clinical audit: A label that sticks. Equine Veterinary Journal, 47 (3), pp. 257-259