Apply

| Site: | Learn: free, high quality, CPD for the veterinary profession |

| Course: | EBVM Learning |

| Book: | Apply |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 15 February 2026, 2:58 AM |

1. Introduction

Once you have Acquired and Appraised the evidence on your particular clinical question, it is important to determine whether the answers you have generated can be applied to your circumstances: the clinic, location or country where you work, the case in front of you and/or the availability of therapies, and the individual needs of the owner. The application of evidence into practice can sometimes be challenging, as you will see in this section.

By the end of this section you will be able to:

- use a structured framework to determine whether the evidence is applicable to you, your patients, your environment and the owner

- develop clinical practice guidelines and protocols

- describe ways of communicating evidence to colleagues and clients.

2. Applying evidence to practice

It has been shown that implementation of evidence into practice is one of the most challenging things to do when compared with finding the evidence and appraising it (Bergus et al., 2004).

There are a number of reasons why it is difficult to apply evidence to practice, but it ultimately comes down to the availability of essential resources (Sackett and Straus, 1996) and the motivation of the individual clinician to make the changes (Kiefe et al., 2001).

Clinicians are trained to assimilate information gathered through taking a clinical history, performing a clinical examination on an animal or group of animals, interpreting diagnostic tests, monitoring previous responses to treatments and understanding client circumstances and expectations (Holmes and Cockcroft, 2004). Integrating evidence works on the same principles that veterinarians use every day, with the evidence becoming a component of the decision-making, alongside the circumstances of the owner and animal in front of you. Through integrating evidence, clinicians continually adapt and update their practice over time.

Example: Is it necessary to measure coagulation parameters before liver biopsy, or not?

In the past, it was recommended that clotting times were evaluated prior to performing a liver biopsy in the horse. There is a risk of haemorrhage associated with the procedure, and in ensuring horses had normal coagulation parameters, this risk was perceived to be lower.

However, measuring clotting times was an added expense and delayed the liver biopsy procedure, sometimes putting clients off performing this important diagnostic step. In 2008 evidence emerged that the risk of haemorrhage was both lower than previously thought, and unrelated to coagulation abnormalities (Johns and Sweeney, 2008). This evidence was rapidly incorporated into practice and now clients are only offered pre-biopsy clotting profiles where there is overt evidence of a clotting disorder (bleeding diatheses).

3. Individualised application of the evidence into practice

Consider the relevance of the evidence to your individual clinical scenario

You may not realise it, but you have been considering the relevance of the evidence right from developing your (S)PICO question at the start of this tutorial in Ask. Developing a well-structured (S)PICO then enabled you to Acquire evidence relevant to your clinical scenario. In section Appraise you decided whether this relevant evidence was of sufficient quality to Apply to your clinical scenario. If you are still unsure whether the evidence you have found is relevant, the following section will help you make a decision.

How relevant is the evidence?

When you read a study, you must make a judgement about how similar your patient is to the population or sample being examined in that particular study, and whether that study is worth considering for the individual circumstances in front of you.

Since a perfect study examining the whole population of animals you are interested in will rarely exist (especially in veterinary medicine!), it is up to you to decide if the evidence you have found is pertinent to your individual clinical question. Studies are often conducted on a number of subject animals and may therefore only be truly representative of a particular subset of a particular population of animals.

Some pertinent questions to ask may be:

- Does the population of animals in the study represent the type of animals that you see (e.g. animals seen at referral practices versus first opinion practices)?

- If the disease is caused by an infectious agent, are there important differences in strains, serotypes, or antimicrobial resistance patterns in the study area versus your practice area?

- Does the evidence focus on animals with single morbidities (as opposed to animals with comorbidities)?

- Does the evidence in the study focus on using one therapy versus combinations of therapies?

Thinking about how to apply the evidence from published studies to the individual animal, or group of animals you are working with raises four different questions, as outlined by Del Mar et al. (2008):

- What are the potential effects of treatment, both beneficial and harmful?

- Are there differences in the effects of treatments on different sub-groups of animals?

- Are there differences in levels of risk between different groups/sub-groups of animals?

- How do the benefits and harms relate to the individual animal or group of animals you have in front of you?

Clinical scenario

The following example will illustrate these four questions using a clinical scenario about the use of analgesic products for calf dehorning.

Click on each of the following headings to expand the text.

1. What are the potential effects of treatment, both beneficial and harmful? Click to expand

When making clinical decisions, it is important for veterinarians to identify the best evidence based on the benefits and harms of any interventions proposed.

Clinical Scenario

Calf-dehorning example

In some countries, long-acting analgesic products are not approved for pain relief in livestock. Some of these countries allow veterinarians to use medicines in an off-licence capacity, when the health of the animal is threatened and when the veterinarian determines that a particular drug is indicated. Extra-label drug usage, however, is not permitted if it results in violating food residue legislation.

Conversely, in many countries, both long-acting and short-acting products are approved as therapy to provide pain relief.

Because you have recently begun working at a practice that has not historically used analgesia for long-term pain relief post-dehorning in cattle, you wonder if you should propose using a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) for calves less than 6 months of age being dehorned, and if so, which NSAID would be preferable, parenteral flunixin or meloxicam? You search the literature and find two references which appear to be particularly relevant to this question:

- Heinrich, A. et al. (2010) The effect of meloxicam on behavior and pain sensitivity of dairy calves following cautery dehorning with a local anesthetic. Journal of Dairy Science, 93 (6), pp. 2450-2457. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2009-2813

- Fraccaro, E. et al. (2013) A study to compare circulating flunixin, meloxicam and gabapentin concentrations with prostaglandin E₂ levels in calves undergoing dehorning. Research in Veterinary Science, 95 (1), pp. 204-211. Available from: https://aperto.unito.it/handle/2318/131393#.X64vjmj7RPY [Accessed 13 October 2020]

In the first study (Heinrich et al., 2010), you note that meloxicam (0.5 mg/kg) was shown to significantly prevent the relapse of pain after the effect of a cornual block had worn off in calves undergoing dehorning with cautery when compared to placebo-treated calves. Pain was measured by reduced sensitivity to pressure, ear-flicking and head-shaking, and meloxicam-treated calves were significantly different from calves receiving a placebo (p<0.05). This research was done on Holstein heifer calves that were six weeks of age.

The second study (Fraccaro et al., 2013) described significantly lower blood prostaglandin E2 concentrations in the flunixin-treated (2.2 mg/kg) group compared to the placebo group after surgical/cautery dehorning; the difference between concentrations in the meloxicam group and the placebo group was not statistically significant. However, meloxicam had a 2½ times longer half-life than flunixin, suggesting that its effect should last longer. This research was done on Holstein steer calves that were six months of age.

When appraising the relevance of this evidence, you consider a number of things:

- Both studies were performed in cattle.

- Heinrich’s study was undertaken in Ontario, Canada, while Fraccaro’s study was done in Kansas, USA. Again, you think it is unlikely that the region would make a difference in interpreting the results of these particular studies. Location will not have an impact on comparing analgesia effects.

- Heinrich’s study was undertaken in a dairy production system, while Fraccaro’s study was in a beef production system. You consider this, but decide that it is unlikely that the production system would make a difference in interpreting these study results.

- Both studies utilised research animals, although, again, you consider it unlikely that the source of animals would make a difference in interpreting the study results.

- In both studies, animals were randomly allocated to the treatment groups, minimising biases associated with group allocation.

- Heinrich’s study involved two groups of 30 calves, whilst Fraccaro’s study had much smaller groups (seven calves in each group). It is possible, therefore, that because of the smaller group sizes, the effect of the individual variation of animals within Fraccaro’s study might be more likely to account for some or most of the differences between the groups.

2. Are there differences in the effects of treatments on different sub-groups of animals? Click to expand

Certain sub-groups of animals (e.g. certain age groups) may be more likely to respond either positively or negatively to specific interventions. When thinking about how you might apply the evidence, you will need to consider which sub-groups of animals were utilised in the research being considered.

Clinical Scenario

Calf-dehorning example

Fraccaro’s study showing flunixin was better than meloxicam used a surgical procedure for dehorning, followed by cautery (for bleeders); this procedure was also performed in older calves, whereas Heinrich’s study used cautery dehorning in younger calves. The Fraccaro study also had a small sample size, and only measured changes in a blood parameter (prostaglandin E2), whereas Heinrich’s study used behavioural changes. After considering all of this, you decide that it is unclear whether the age of the calves would alter the interpretation of the studies, but you keep the details in the back of your mind.

3. Are there differences in levels of risk between different groups/sub-groups of animals? Click to expand

By the nature of how and where they are kept, or their innate attributes, different groups or sub-groups of animals may have different levels of immunity and exposure to various pathogens. These differences may lead to different manifestations of disease severity in these different groups.

Clinical Scenario

Calf-dehorning example

It would be difficult to argue that there is a difference in the risk of pain from dehorning between a six-week-old calf or a six-month-old calf. Both ages would feel pain, although one could argue that the size of the horn in a six-week-old calf is smaller than in a six-month-old calf, and therefore the dehorning procedure would be more painful in a six-month-old calf than a six-week-old calf. However, there is no evidence that age groups would make a difference to treatment response in this particular case and scientific question.

4. How do the benefits and harms relate to the individual animal or group of animals you have in front of you? Click to expand

It is down to you as the veterinarian to make a judgement on the applicability of the research findings to your patients, which could involve a number of considerations. In addition to the research results, you might choose to reflect on your previous experience with similar cases, or to have a more in-depth discussion with the owner. You might also want to discuss the matter with colleagues, or consult an online forum to gain a broader view of the question at hand.

Clinical Scenario

Calf-dehorning example

It is unclear whether different groups of animals would make a difference in interpreting the study results. Perhaps the type of dehorning could make a difference in the interpretation of the results. The combination of surgical dehorning and cauterization of bleeders would be expected to produce more tissue trauma and pain than simple cauterization, as well as on-going infection and its associated pain.

Another pertinent question to ask might be whether or not the findings of the studies are clinically relevant to your case, that is, will they really make a difference to the animal(s) in front of you? Once again, it is up to you to make a judgement about whether or not the outcomes measured would be expected to translate into meaningful clinical benefits to the patient and owner in front of you.

Clinical Scenario

Calf-dehorning example

Because Heinrich’s study assessed behavioural changes in six-week-old calves, it would seem to be more clinically relevant than Fraccaro’s study, where only changes in blood parameters were measured in six-month-old calves.

If you do not think the evidence from the papers you are considering is relevant enough to apply to the animal or group of animals you are treating, you can have a discussion with the owner of the animal(s) about the uncertainties around the options available (Legare 2009). Additionally, you may choose to:

- Rely on the information in other forms of evidence such as textbooks, and online websites

- Do what you would normally do in these circumstances before you were aware of the published evidence, or

- Rely on your local clinic’s advice or guidelines, or advice from colleagues who have handled these types of clinical problems before.

Clinical Scenario

Calf-dehorning example

The Heinrich study would seem to provide relevant evidence in relation to the particular circumstance in front of you, while the Fraccaro study suggests that meloxicam could potentially last longer than flunixin. The Fraccaro study also only provides blood-related evidence of flunixin perhaps being better than meloxicam with respect to prostaglandin E2 concentrations. Without any clinically relevant observations, however, this evidence would not be enough to suggest that it is preferred over meloxicam, even in six-month-old Holstein steer calves being surgically dehorned.

3.1. Consider the individual circumstances of your clinical scenario

Now that you have decided whether your evidence is relevant to your clinical question, you need to decide whether the evidence is applicable to your individual set of circumstances.

Let’s revisit the definition of evidence-based veterinary medicine:

Evidence-based veterinary medicine is the use of the best relevant evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise to make the best possible decision about a veterinary patient. The circumstances of each patient, and the circumstances and values of the owner/carer, must also be considered when making an evidence-based decision. (Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine)

Now you need to use your professional knowledge, skills and judgement to consider whether the evidence is applicable to the individual set of circumstances surrounding your clinical dilemma. Listed below are some of those circumstances to be considered:

- the patient–(owner)–clinician relationship

- a sensitivity to the human-animal bond

- expectations of end-of-life care

- animal welfare

- veterinary business practice

- funding and insurance models

- equipment limitations

- varying cultural beliefs

- clinician confidence in new procedure or treatment protocol…

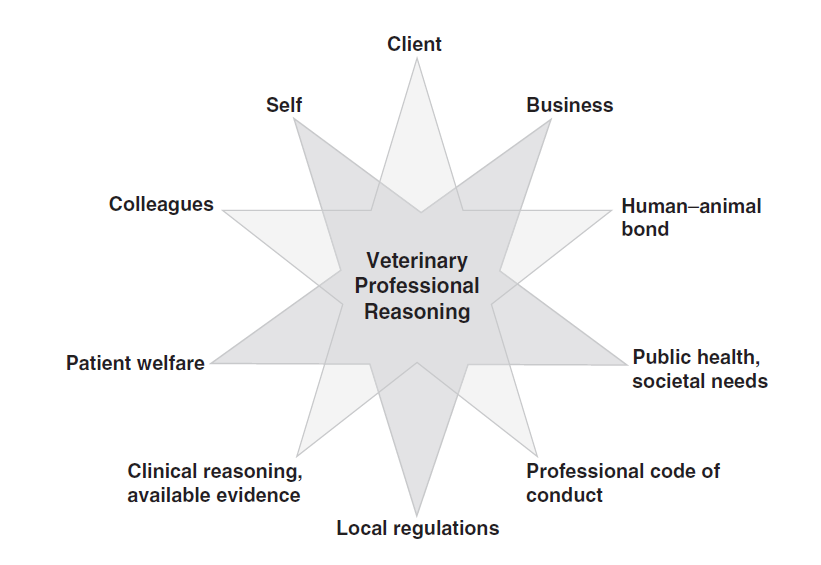

It is useful to apply a framework within which to consider these factors. Armitage-Chan (2020) has developed such a framework which takes the clinician through a step-by-step process of ‘professional reasoning’ (Figure 1) and this could be used as a guide when integrating evidence into practice. Through a process of information gathering, the clinician must consider all the stakeholders involved in the decision-making process, represented by the star diagram below.

Figure 1: Stakeholders in veterinary professional reasoning

(from Armitage-Chan, 2020; included with permission from the author, the Journal of Veterinary Medical Education and the University of Toronto Press)

The diagram can be helpful to consider how various dilemmas may arise; sometimes your clinical decision may not fit with the best evidence, it may not always be the same as that of your colleagues.

Recent work on identity formation suggests that when veterinarians act in a way which doesn’t sit well with their personal goals and values, they can experience identity dissonance, which can lead to anxiety and a lack of psychological well-being (Armitage-Chan and May, 2019).

It is useful to recognise that there may be multiple, equally valid ways of approaching a clinical scenario. The following examples help to illustrate potential dilemmas that may arise in everyday situations.

Example Scenario

Elderly pet dog – what are the options for the client?

An elderly couple with no pet insurance, present their bitch, Molly, who is unwell. You diagnose an open pyometra. You have read a recent Knowledge Summary with the following clinical bottom line:

Ovariohysterectomy combined with antibiosis is more effective in achieving clinical cure than systemic antibiosis alone. Systemic antibiosis may be associated with recrudescence of the pyometra and the evidence base is weaker for this approach. Read the full Knowledge Summary

You know that surgery would give a better chance of a good short- and long-term outcome for Molly. Your other options are medical management with antibiotics (with a high risk of recurrence, even if successful in the short-term), or euthanasia. Molly is still eating and cardiovascularly stable and the owners have financial limitations to undertaking an ovariohysterectomy.

In this case, together with the owners you decide that you will trial a course of antibiotics with a view to re-assessing Molly regularly and if her condition worsens, she will be euthanised. You might feel uncomfortable with this approach, knowing that surgery could successfully treat the pyometra; you make sure you discuss further options, such as euthanasia, if there is no improvement and warn the owners of the likelihood of recurrence.

Example Scenario

The cost of efficiency

Your interest in infection control led you to read an article in a veterinary nursing publication about using alcohol hand rubs as an alternative to the more traditional hand scrubbing. An online search of the current literature leads you to a knowledge summary with the following clinical bottom line:

The current literature suggests that the use of alcohol hand rubs provide similar, if not better, reductions in bacteria colony forming units [when compared to traditional methods of hand scrubbing], both immediately after hand antisepsis and in the immediate postoperative period. Read the full Knowledge Summary

Using alcohol hand rubs would mean that the time spent ‘scrubbing in’ will be reduced, with the added potential benefit of better compliance and a reduction in patient anaesthetic time, especially when time is more critical.

At the moment the practice buys scrubbing brushes and chlorhexidine which are a similar cost to alcohol hand rub and is considering changing. However, a global pandemic made all alcohol hand rubs very difficult to source resulting in the cost of these products rising, and outweighs what the practice is already paying for scrub brushes and chlorhexidine. Therefore, the practice decides the current protocol (scrubbing with chlorhexidine) will remain in place and the lead nurse is tasked with reviewing the situation (cost and availability of alcohol hand rub) at regular intervals.

3.2. Sharing evidence with your clients

After acquiring as much information as possible, the clinician is required to discuss their decision-making with the relevant parties, such as the client and relevant colleagues.

Shared decision-making (SDM) is receiving more attention in EBM and EBVM; the British Medical Journal included SDM as one its six proposals for EBM’s future in their online EBM toolkit .

There are a number of ways to share and discuss evidence with your clients through verbal and written communication channels.

In-person discussions

Owners may be wary of new treatments or different approaches, particularly if they have had previous success through other treatment approaches, so it will be of benefit to spend time discussing any new evidence with them. Discussing evidence with clients will potentially improve uptake of the new approach and owner compliance in seeing it through.

Electronic and/or paper copies of journal articles

For clients who have some medical or scientific background, providing electronic and/or hard copies of open access literature relevant to the discussion can add to your credibility on the subject and provide convincing data to the clients.

Client leaflets

Many practices are producing their own client leaflets to educate owners. Investigate the resources available to you in your practice. Maybe you could develop them?

Click to expand and read the scenario-based examples below.

Farm example Click to expand

You visit a farm with a scouring calf. You have recently read a BestBET which has the clinical bottom line:

Feeding milk in addition to an oral rehydration solution may help scouring calves to maintain or even gain weight when compared with feeding oral rehydration solution alone. Read the full BestBET

You discuss this with the farmer, who usually withholds milk from scouring calves. During the discussion you determine the reasons why the farmer withholds milk and what that approach is based on. The discussion helps you to understand why the farmer may be reluctant to change and enables you to make a good case for adopting the recommendations of the new evidence. As a result, you decide together that you will trial the combination of milk and oral fluids.

Small animal example Click to expand

Mrs. Lee has been using a glucosamine supplement for the last two years with the aim of reducing the clinical signs of osteoarthritis in her pet dog, Barney. You read a BestBET and a ‘What is the Evidence?’ publication in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association outlining that this supplement may not be effective. Mrs. Lee has been using the product for some time and is convinced that there are some benefits gained by using it, although she still feels that Barney is reluctant to walk as far.

You take time to discuss with Mrs Lee the benefits of other therapies (such as carprofen or other NSAIDs) for reducing the clinical signs of osteoarthritis which have been recognised in research studies. During the discussion, you provide her with the opportunity to ask questions about the expectations of the treatment, the financial implications and any potential risks for her pet dog. You also find out what outcome is important to Mrs Lee from treating her dog; she reveals that she misses their daily walks to the park now he can’t walk as far and this is causing her some loneliness.

You think NSAIDs could manage Barney’s pain better and enable him to walk to the park again. You are prudent to guide the process and expectations of the treatment change. You develop a structured treatment regime in conjunction with Mrs. Lee, based on high-quality evidence, to implement treatment with NSAIDs, stopping the glucosamine, for a “test” period. It is crucial that together, you identify re-assessment points and schedule check-ups proactively so that Mrs. Lee can provide you with feedback about the new regime and how it is performing in relation to how comfortable Barney is.

A list of sources of evidence summaries can be found in Table 2 of a paper by Brennan et al. (2020) .

4. Developing clinical practice guidelines and protocols

By discussing cases and how they are managed with other staff within your practice, it may become apparent that having some structured guidance based on the existing evidence may be beneficial. If the evidence doesn’t exist, making sure that the practice is approaching these type of cases in a broadly similar way will be important. One way of doing this is by creating clinical practice guidelines and protocols.

Through the development of unambiguous and concise clinical guidelines and protocols, practitioners can be motivated to trial new ways of approaching a case. Both protocols and guidelines support clinician decision-making and are evidence based.

Despite the terms frequently being used interchangeably, protocols and guidelines are not the same thing. As the names imply, protocols are much more rigid rules compared to more flexible guidelines. However, both should be clear and concise and include sufficient information so that they can be understood without reference to other supporting materials.

Guidelines

Clinical guidelines are intended to provide information to assist decision making in the management of a case based on an appraisal of the current best evidence. (Hewitt-Taylor, 2004)

Clinical guideline recommendations should be unambiguous, consistent and define target patient populations and expected clinical outcomes. Successful guidelines are simple documents that guide veterinarians through a process (be that diagnostic, treatment or any other process), without describing how each procedure is delivered to a patient. Guidelines can assist communication of evidence within a practice or community of veterinarians.

Protocols

Protocols are rigid statements or rules which must be adhered to. A protocol sets out a precise sequence of activities in the management of a specific clinical condition (Hewitt-Taylor, 2004). In areas such as biosecurity, surgical checklists, radiation safety and operating procedures for equipment, protocols are more appropriate than guidelines.

You might have an area of practice in which you feel improvements could be made. Consider the following example:

Your practice has recently invested in laparoscopic equipment. You are the only vet currently experienced and confident in performing laparoscopic ovariectomy in dogs. You wonder whether a change in practice from open ovariectomy would be beneficial for the practice’s patients. You find a relevant BestBET supporting this theory with the following clinical bottom line:

In small dogs (<10kg), use of a laparoscopic ovariectomy technique may lead to greater activity levels in the 48 hour post-operative period than if ovariectomy is performed using a conventional midline open technique. (Read the full BestBET )

You also find a knowledge summary comparing ovariectomy (OVE) with ovariohysterectomy (OVH), which concludes:

whilst the evidence does suggest OVE may be associated with some modest improvement in surgical time and incision length, due to the small sample sizes and varying techniques used, further studies are required before definitive conclusions can be made. (Read the full Knowledge Summary )

The practice team agrees with your recommendation and decides to adopt laparoscopic surgery more widely. To support the effective implementation of this change, you produce a clinical protocol outlining the important steps in setting up the equipment and performing the laparoscopic technique and set up training for the rest of the team, including surgical training for operating vets and nurses and informing support staff who may be involved in communicating with owners.

Whether you choose to develop a protocol or a guideline, there are a number of steps involved:

- Identify the specific clinical scenario for which you wish to address.

- Select the team of practice staff interested in the specific topic to support the evidence gathering for the guidelines or protocol.

- Search for existing research-based guidelines (don’t reinvent the wheel). If nothing appropriate exists, then search the evidence on the specific clinical scenario. You will need to Ask a clinical question and Acquire and Appraise that evidence.

- Produce your practice guidelines or protocol based on your evidence. They should be short, straightforward, logical, and focus on the needs of the client/patient; have realistic times and outcome goals; and highlight roles and responsibilities, with measurable outcomes that can be assessed).

- Pilot the guidelines or protocol within a defined time/space and modify the protocol as needed from the pilot.

- Implement the guidelines or protocol, including any training needed.

- Monitor the compliance and effectiveness of the guidelines or protocol.

- Conduct an annual or biannual review of the compliance and effectiveness of the guidelines or protocol.

Figure 4: Process for developing guidelines or protocol

The use of clinical practice guidelines and protocols provides practitioners with a reflective tool. Periodically and systematically assessing the effectiveness is important to ensure that they have had the desired effect on patient outcomes and as part of practice quality improvement, or clinical governance. Techniques for doing this assessment can be found in the next stage of the EBVM cycle under Assess.

5. What factors should I consider before implementing a change?

Read on for additional considerations on how you might approach implementing changes to your team’s clinical practice.

Any changes, however small, can have a large impact; this may impact on you individually but also at the level of the practice. It is impossible to anticipate all the potential effects of a change, but it is important to consider as much detail as you can prior to implementing any changes.

There are other factors you should take into account when considering implementing changes to your team’s clinical practice. It is possible that your colleagues may not agree with the changes that you are suggesting. Many barriers, for example time pressures, have been highlighted in the literature in relation to reasons why evidence is not applied into practice (Legare, 2009). Don’t let this stop you from making a change individually to the patients that are in your care. After discussion with your colleagues, perhaps at a practice meeting, or journal club, you might influence others to embrace changes too.

Research looking at the success of change implementation in the medical field (Haley et al., 2012) identified factors which facilitated and hindered proposed actions. We will explore each of these challenges in more detail:

Who Click to expand

Reflect on previous episodes of ‘change’ within your practice; who was for the change? who was against the change? what were the facilitators and barriers to change?

You have noticed that, on occasion, the equine vets in your practice approach lameness cases differently, leading to confusion amongst the support staff in your clinic as to what equipment and consumables they should be preparing. You are interested in developing an evidence-based standardised framework that the vets in your practice can follow for carrying out lameness work-ups. You expect this approach to lead to fewer misdiagnoses, and it should assist the support staff in their preparation.

You made an attempt at introducing a new framework a year or so ago, but as the junior vet, you got some resistance from the two senior vets in the practice.

Since the support staff are struggling with the preparation for these assessments, you decide to talk to one of them, Lizzie, who has worked in the practice for twenty years, to talk her through your suggestion. The senior vets seem more receptive to the idea when you bring it up again with Lizzie’s support.

When Click to expand

Ensure that you have highlighted a specific time that can be used to make any changes; is it easy for other things to take priority in a busy practice.

Pick the most appropriate time to implement the changes. For example, if it requires others to help, make sure it isn’t during a busy period.

The senior vets agree to try the new framework. However, the initial timing for implementation was during a week when one of the vets was on holidays and the other was at a continuing education course, and you were busy with the additional work, so you abandoned your plans after the first day.

Thinking strategically about timing for the new framework, you know that in a month’s time, a new graduate is joining the practice and will be spending the first week with you on visits, getting to know the clients. The practice diary is being kept quiet to allow the new graduate more time on visits. You think this may be a good time to trial the framework as there will be less time pressure on you, and it will probably be of benefit for the new graduate also.

What Click to expand

Ensure that you are clear as to what you are changing, and what actions are required. It is beneficial to make a note of any changes in order to compare the associated outcomes at a later stage, for example, what was done, the date, dose rates, approaches attempted. You may consider a more formalised framework, such as writing practice guidelines (see below).

Your aim is to get the vets to follow a lameness work-up framework, which will contain the steps they carry out anyway, but perhaps in a slightly different order to how they might have approached these cases previously, with slightly different equipment and consumables.

Communicate the specific details of the suggested changes with the vets and support staff in the practice to make sure everyone is clear about the changes you are suggesting. You could also run an initial pilot where you trial the framework first prior to getting the others involved.

How Click to expand

If possible, plan to implement small incremental changes one at a time, particularly if the changes are required to a number of areas within the practice, to prevent staff feeling overwhelmed by too much change.

Make sure you have everything organised beforehand, for example, the necessary equipment, therapies, resources, people, to make the transition as seamless as possible.

You plan to trial the framework for forelimb lameness to start with. You ask the new graduate shadowing you to feedback on how well the framework works.

With positive feedback on the forelimb lameness framework, you may be in a good position to implement a hindlimb lameness framework in future.

As you consider all the factors which are involved in your strategy for change, it is useful to record any changes you are implementing. This can be done informally, or you may decide to adopt a more formal and evidence-based approach, through producing clinical guidelines. The final and important step in the EBVM cycle is to Assess these changes, covered in the next section.

7. Summary

Learning outcomes

You should now be more familiar with how to:

- use a structured framework to determine whether the evidence is applicable to you, your patients, your environment and the owner

- develop clinical practice guidelines and protocols

- describe ways of communicating evidence to colleagues and clients.

8. References

Armitage-Chan, E. (2020) Best practice in supporting professional identity formation: Use of a professional reasoning framework. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 47 (2), pp. 125-136

Armitage-Chan, E. and May, S. (2019). The veterinary identity: A time and context model. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 46 (2), pp. 153-162

Bergus, G. et al. (2004) Appraising and applying evidence about a diagnostic test during a performance-based assessment. BMC Medical Education, 4:20. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-4-20

Brennan, M.L. et al. (2020) Critically appraised topics (CATs) in veterinary medicine: Applying evidence in clinical practice. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 7:314. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00314 [Accessed 16 November 2020]

What is evidence-based veterinary medicine? [Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine (CEVM)] [online] Available from: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/cevm/about-the-cevm/evidence-based-veterinary-medicine-(evm).aspx

Del Mar, C., Doust, J. and Glasziou, P. (2008) Clinical Thinking: Evidence, Communication and Decision-making. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Fraccaro, E. et al. (2013) A study to compare circulating flunixin, meloxicam and gabapentin concentrations with prostaglandin E2 levels in calves undergoing dehorning. Research in Veterinary Science, 95 (1), pp. 204-211. Available from: https://aperto.unito.it/handle/2318/131393#.X64vjmj7RPY [Accessed 16 November 2020]

Haley, M. et al. (2012) Implementing evidence in practice: do action lists work? Education for Primary Care, 23 (2), pp. 107-114

Heinrich, A. et al. (2010) The effect of meloxicam on behaviour and pain sensitivity of dairy calves following cautery dehorning with a local anaesthetic. Journal of Dairy Science, 93 (6), pp. 2450-2457. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2009-2813 [Accessed 14 October 2020]

Hewitt-Taylor, J. (2004) Clinical guidelines and care protocols. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 20 (1), pp. 45-52

Holmes, M. and Cockcroft, P. (2004) Evidence-based veterinary medicine 1. Why is it important and what skills are needed? In Practice, 26 (1), pp. 28-33

Johns I.C. and Sweeney, R.W. (2008) Coagulation abnormalities and complications after percutaneous liver biopsy in horses. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 22 (1), pp. 185-189

Kiefe, C. I. et al. (2001) Improving quality improvement using achievable benchmarks for physician feedback: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285 (22), pp. 2871-2879

Legare, F. (2009) Assessing barriers and facilitators to knowledge use. In: Graham, I., Straus, S. and Tetroe, J. Knowledge Translation in Health Care: Moving from Evidence to Practice. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell

Mullan, S. and Fawcett, A. (2017) Veterinary Ethics: Navigating Tough Cases. Sheffield, UK: 5M Publishing

Sackett, D. L. and Straus, S. E. (1996) Finding and applying evidence during clinical rounds: the ‘evidence cart’. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280 (15), pp. 1336-1338

Scott, I. A. and Glasziou, P. P. (2012) Improving effectiveness of clinical medicine: the need for better transition of science into practice. Medical Journal of Australia, 197 (7), pp. 374-378