Acquire

| Site: | Learn: free, high quality, CPD for the veterinary profession |

| Course: | EBVM Learning |

| Book: | Acquire |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 22 February 2026, 11:46 AM |

1. Acquiring evidence

Formal methods for searching for evidence have been developed to try and maximise retrieval of the best available evidence and to minimise bias in clinical decision-making.

Evidence searches aim to be systematic. They follow standardised methods so that as much as possible of the relevant evidence is reviewed, rather than the reader consulting the most easily available evidence or hand-picking evidence that supports a pre-existing, potentially biased, approach.

Evidence searches draw on the well-established methodology of evidence-based human medicine (EBM). Standards for reporting an evidence search have also emerged, allowing searches to be explicit and reproducible so that others can assess whether decisions were well founded, and whether new evidence has emerged that might necessitate a change in clinical practice.

The Ask section introduced the first step – to pose your clinical question in a structured way, demonstrated with the PICO format (or SPICO when species is included with patient). The next step is to build a search strategy, which means choosing the best sources of evidence and searching those sources in the most efficient way.

This Acquire section will describe those methods for searching and reporting in some detail, with a view to giving comprehensive advice, but it is recognised that different advice is needed for those in universities, and those who are vets in practice; and for those doing a quick evidence search for a clinical setting and those wishing to publish an evidence review. Decide what your searching requirements are and navigate to the most relevant sections.

It can help to look at some examples of best practice in evidence searches, to see what we are aiming for.

To see examples, take a look at the search strategies reported from Veterinary Evidence and BestBETs for Vets using the links below.

Cats Click to expand

Cattle Click to expand

Does pasteurising colostrum reduce Johne's disease morbidity in adult cattle?

Dogs Click to expand

Do palliative steroids prolong survival in dogs with multicentric lymphoma?

Horses Click to expand

Does tendon firing quicken time to recovery for superficial digital flexor tendon injury?

Poultry Click to expand

Rabbits Click to expand

Selamectin versus ivermectin for Cheyletiellosis in pet rabbits

2. What sources of evidence are there?

Where can evidence be found to help answer clinical questions?

EBVM links the results of research to the practice of veterinary medicine, so we need to know where to find the best, most relevant research for each clinical question.

It is helpful to understand the difference between primary and secondary sources, and between published information and grey literature:

1. Published scientific research

Primary sources

Primary sources of evidence offer a first-hand account of research or practice written by those who were directly connected to it. In EBVM this typically means journal articles, reports or conference papers that describe:

- research studies (quantitative and/or qualitative)

- clinical trials

- case studies and case reports.

Secondary sources

Secondary sources are created later by third-party authors who summarise or synthesise primary sources and often comment on them. These are discussed in more detail in the Secondary sources section and include:

- evidence syntheses (including systematic reviews, meta-analyses and evidence summaries e.g. Knowledge Summaries)

- clinical practice guidelines

- textbooks and manuals.

2. Grey literature

Grey literature is research material that is not formally published within the conventional, commercial publishing channels. Examples include:

- reports and working papers (e.g. from government agencies)

- theses and dissertations

- lecture notes

- websites, blogs and social media posts.

Traditionally, peer-reviewed scientific journals, and the bibliographic databases that index them, have been considered the best source of evidence. Research into publication bias (Glanville et al., 2015) suggests a need to go beyond these sources alone, as a proportion of research will not be published in peer-reviewed journals.

You may have access to books, conference papers or case reports…and clinical records and practice data are already being used to help veterinary professionals make evidence-based decisions at the point of care (Brodbelt, 2014).

The key is to use the best evidence available to you.

2.1. Secondary sources

How can secondary sources help vets to be evidence-based?

A vet in practice may not have the time to do a detailed search of the primary research literature, but EBVM can help by providing secondary sources that synthesise the best available evidence to give practitioners quick answers to clinical questions.

For those with more time, EBVM provides standard methodologies to systematically search for and analyse scientific studies to answer a clinical question and create outputs that can benefit the professional community.

The main outputs of EBVM are evidence syntheses:

Systematic reviews

Systematic reviews of the scientific literature aim to find every single scientific study relating to the PICO question, allowing you to draw recommendations from the widest body of evidence.

A systematic review is performed in a highly structured way, with the question and methods clearly defined in advance to try to minimise any bias that the reviewer may have in selecting and interpreting the research.

Meta-analyses

Sometimes the systematic review is extended to include an analysis of the quantitative data sets from the research studies found (where they are sufficiently homogeneous) to provide a single estimate at the end with an indication of the confidence limits that can be applied to the combined data.

Evidence summaries

A full systematic review is a major undertaking and typically involves a team of people, taking many months to complete, and so simpler methodologies have emerged to create quick and achievable summaries of the current best evidence for a clinical question. These can have different names, such as:

- Knowledge Summaries

- Critically Appraised Topics (CATs)

- BestBETs.

Clinical practice guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines are concise recommendations for healthcare professionals on how to care for patients with specific conditions, which are often based on systematic reviews or evidence syntheses.

Clinical guidelines provide a quick and easy way for busy practitioners to ensure their clinical decisions are based on the best available evidence without having to do the legwork of EBVM themselves.

Read more about how to produce these for your practice in Apply.

Manuals, textbooks and other publications

Systematic reviews and evidence summaries are still relatively uncommon in veterinary medicine, and so you will often need to search other sources, such as textbooks or the primary literature. Although textbooks and manuals use less formal methods and may not contain the most up-to-date evidence, they can still contain valuable information, and may be the best source of evidence available to answer some questions.

Read more about the Levels of Evidence in the Appraise section .

Evidence-based medicine: formal methodologies

For those wishing to create systematic reviews or evidence summaries, formal methodologies have been developed to provide standards to minimise bias.

Two key sources to be aware of:

- The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions outlines the formal methodologies developed for evidence-based (human) medicine, developed by Cochrane.

- How to Write a Knowledge Summary shows how the Cochrane methods have been adapted for the veterinary profession by RCVS Knowledge.

A special issue of the journal Zoonoses and Public Health focuses on the methodology and is freely available online: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis in Animal Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine .

Where you decide to search for EBVM will depend on what you are looking for:

If you are a busy practitioner, you may just want to do a quick search for evidence that others have written to see if there is a quick answer to your question. Ideally you are looking for an evidence synthesis, but in the absence of this, then you may turn to primary sources.

If you are a student or researcher, or a practitioner with more time, you might want to learn the formal methodologies of EBVM and do a comprehensive search to create a new systematic review or evidence summary.

2.2. Evidence syntheses

What are the key sources of secondary evidence for veterinary sciences?

Your first search should be for secondary evidence, as if there is already a high-quality, up-to-date systematic review or evidence summary already published, there may be no need to search any further.

Evidence syntheses are a relatively new development for the veterinary profession, but more are being published each year, with growing collections now available online.

Evidence summaries

Freely available:

Although there are still only relatively small numbers key places to search are:

- Veterinary Evidence — an online, open-access, peer-reviewed journal that publishes EBVM articles, including Knowledge Summaries and systematic reviews. It is published by RCVS Knowledge, the charity partner of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) in the UK.

- BestBETs for Vets — a freely accessible database of Best Evidence Topics (BestBETS). It is published by the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine at the University of Nottingham, UK.

- Equine Veterinary Journal: Clinical Evidence in Equine Practice — online collection lists systematic reviews and critically appraised topics.

- Veterinary Record – this UK journal has a regular column called 'Evaluating the evidence' which includes evidence syntheses.

- Zoonoses and Public Health — Special issue: systematic reviews and meta-analysis in animal agriculture and veterinary medicine

Systematic reviews

Systematic reviews are considered the highest level of evidence. If you can find a recent systematic review that answers your specific question this will be a great help, as someone else has already spent the time doing the search and appraisal work for you.

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews is a key source of systematic reviews in human medicine, and there is now a will in the veterinary community to try and build something comparable. In these early days of EBVM, a direct comparator of Cochrane does not exist for veterinary medicine, but the VetSRev database (see below) has been up and running since 2013.

The VetSRev database is a freely accessible online database of citations for systematic reviews relevant to veterinary medicine and science. Produced by the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine at the University of Nottingham, UK, it aims to disseminate information about existing systematic reviews to the veterinary community. You may be surprised by the number that already exist, and the number published each year is growing.

Clinical practice guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines can be evidence-based if they are based on a review of the literature and critical appraisal of the evidence. See the Assess section for more information.

Examples include:

- Treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: 2015 updated guidelines from the International Committee on Allergic Diseases of Animals (ICADA) .

- The RECOVER guidelines on veterinary CPR, the first evidence-based recommendations to resuscitate dogs and cats in cardiac arrest, produced by the American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care and the Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care Society .

-

AGREE provides tools for the creation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines .

Most GPs in human medicine use systematic reviews, evidence summaries, and guidelines to answer their clinical questions. They don’t do many, if any, searches of the primary literature themselves. For example, in the UK they may rely on NICE Evidence Search.

2.3. Primary sources

When would it make sense to search the primary sources?

If no secondary evidence exists in an evidence summary or systematic review, then it might be helpful to search the primary sources. Searching the primary sources is essential for those creating an evidence synthesis themselves.

"Veterinary practitioners may believe that there is not enough time to search for science-based information while managing cases, but these perceptions often change after experiencing the effect this new-found knowledge has on treatment response by the patient.” (Gibbons and Mayer, 2009)

The EBVM methodology developed when scientific research studies were published online, and when sophisticated search tools made focused searching possible.

Bibliographic databases

Bibliographic databases are search tools designed to help you search across the research literature (journal articles, books, conference papers, etc.).

They can focus on a particular subject area or be interdisciplinary. Each database systematically indexes articles from a given list of journals and other scholarly and professional publications, and so provides the most effective and efficient means for searching the scientific literature.

Each database searches a different set of journals and publications, but they are explicit about their coverage and you can check to see what is included.

It should be remembered that databases are tools to identify relevant papers. While some databases contain full-text articles, many do not, and so you will also need to find ways to access the papers you wish to read; how to do so is covered later in this section.

Journals

If you don’t have access to subscription databases then you can refer directly to the journals that you do have access to, acknowledging that you will not be retrieving the broad spectrum of evidence.

2.4. Bibliographic databases

What are the key databases for veterinary searches?

Key databases that index journals relating to veterinary sciences are listed below, with an indication of subject coverage and access. Links to the publishers’ websites are also given, where further information about each database can be found.

The database CAB Abstracts has been shown to give the greatest percentage coverage of journals with veterinary content: 90.2% (Grindlay et al., 2012), and so would be seen by many as the key database for EBVM.

However, given the interdisciplinary nature of veterinary sciences, journals from other biomedical disciplines may also provide useful evidence, alongside the veterinary-specific journals. Therefore, to ensure that you retrieve as much of the published evidence on your topic as possible, you should use CAB Abstracts and then at least one other database.

RCVS Knowledge asks authors of Knowledge Summaries to search CAB Abstracts (1973–current) and PubMed as a minimum. Note: if you only use PubMed, you risk missing a large proportion of veterinary journals that are not included in PubMed.

For examples of ‘Journals List’ which indicates the scope and subject coverage of a database, see the List of Journals Indexed for MEDLINE or the Veterinary Journals Indexed in PubMed .

Because veterinary research is published throughout a broad range of veterinary, agricultural, human medical, and basic science journals, no one database comprehensively provides indexing and abstracting to all literature relevant to the clinical question. Thus, careful searching using a wide variety of information resources is required. (Murphy, 2007)

Additional sources of evidence

There are, of course, other sources of veterinary evidence, but we cannot include everything here. Some useful lists exist:

- RCVS Knowledge: sources of evidence – maintained by the library staff at RCVS Knowledge

- Veterinary Science Search and Veterinary Information Resources – maintained by the U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Information for Veterinary Professionals – maintained by Texas A&M University.

Database delivery platforms and interfaces

Some of the databases listed above are available to purchase from different database providers and via different platforms. The different delivery platforms can offer different search interfaces, which may offer enhanced functionality (e.g. clearer presentation of Subject Headings). When reporting a database search, it is important to mention the platform you accessed it on to enable the search to be peer-reviewed and replicated (as different platforms can require different search strategies for optimum searching). Some of the main platforms, with links to the suppliers, are given below:

2.5. Internet search tools

Can’t we just rely on internet search tools like Google or Google Scholar for finding evidence?

To some extent this depends on you and how much time you have to browse the internet for information and analyse what you find, to decide whether or not you can trust it. If internet searching is your only option, it is better than nothing!

Some of the key issues are:

A lack of peer-review on the internet Click to expand

General internet search tools do not confine themselves to peer-reviewed information from the academic and scientific communities and so, while they will include links to some high-quality evidence, the amount of time it will take to locate this amid everything else that is listed can make them inefficient. The onus is on you to learn how to search them efficiently, and to sift through the results and analyse them to discern the validity and currency of the evidence.

Search engines cannot discriminate predatory journals Click to expand

Disreputable publishers, sometimes referred to as 'predatory', have emerged online in recent years. They exploit the open access model of publishing where the author pays an Article Publishing Charge (APC). The disreputable publisher takes the money but fails to follow through with the peer-review and editing process that is the standard expected from a reputable scientific journal. This has led to a proliferation of freely available poor-quality research. While these 'predatory journals' usually would not meet the inclusion criteria for databases such as MEDLINE, they are included in Google search results. Again, it would require time and effort to weed out articles from predatory journals from your Google results. Databases can offer an efficient means of avoiding articles from predatory journals.

How can I investigate the quality of this journal?

- Is the journal indexed in bibliographic databases like PubMed ?

- Is the journal listed in DOAJ : the Directory of Open Access Journals?

- Use the tools and strategies from Think Check Submit

We cannot be sure search engines search across all the relevant journals systematically or comprehensively Click to expand

Using search engines, you run a risk of missing key evidence, because these tools do not take a systematic approach to indexing in the way bibliographic databases do.

- If your results include an article from a journal, you cannot presume that the search engine looked at all the articles and all the issues of the journal.

- The most useful results may not be first in the list; the results list may give higher ranking to some items because they are paid to.

- The relevant, quality results can be swamped by low-quality results, so it can be very hard to pinpoint what you need.

- Search engines often link to a finite number of results; if key resources were to come lower down the list, we might miss them.

The inability to reproduce your search and results Click to expand

Those producing an evidence synthesis need to report the search strategy, so that it is explicit and reproducible. This is not possible with internet search engines like Google, for reasons described below.

Internet search engines and bibliographic databases work in different ways, and while brilliant for finding information generally, search engines have imitations for EBVM.

Google Click to expand

Google crawls the internet and retrieves results using an algorithm which, for commercial reasons, is a closely guarded secret. We do know Google uses robots rather than biomedical graduates to populate its indexes and does not publish a Journals List we can check to see if key journals in our field are being included, so we cannot be sure it indexes all the relevant journals.

While great for searching for information generally, Google generates searches that are not reproducible – the ranking of search results on Google are subjective and vary according to IP address, location, and previous search history (i.e. which computer is used, where it is located geographically, and the previous searches conducted on it). This cannot be used for situations where a search should be explicit and reproducible, such as that used to produce an evidence synthesis.

Google Scholar Click to expand

Google Scholar is a search engine, not a bibliographic database, but it indexes articles. This means it can reveal useful results, but unlike bibliographic databases, it does not publish a list of the sources it is searching, so we cannot say with confidence we have performed a systematic search of all the relevant veterinary journals.

It searches the full text of web resources, so may retrieve results not found via bibliographic databases (which search the bibliographic data only, e.g. author, title, abstract, keywords). It can also be useful for citation searching.

Wikipedia Click to expand

Google will often give you results from Wikipedia , the online encyclopaedia written collaboratively by internet volunteers. Wikipedia has some great research-based information on it, but anyone with internet access can make changes to Wikipedia articles, and people often contribute anonymously using a pseudonym. This has pros and cons: it can be updated very quickly, and articles are dynamic and so can be updated to reflect new evidence. However, the quality of articles depends on the skill and knowledge of individual authors, which can be hard to ascertain from anonymous contributions.

Databases are more reliable than internet search engines since they focus on scientific literature and list the sources they search. Although internet search engines are free, they are less reliable.

Some bibliographic databases are freely available and will provide a more robust search of the evidence when compared to internet search engines.

3. How do I access the evidence?

How can we access the evidence, given that it isn’t always free?

Scientific publishing is big business and so many of the key sources of information will not be free for everyone to access. It helps to be aware of the different access models.

Databases are generally just a search tool – they contain details of publications but not the full text of the publications themselves. There is therefore a two-step process to acquiring evidence via bibliographic databases:

- getting access to databases

- getting access to the full-text of the publications.

Many of the databases and journals needed for EBVM are not free to access. However, there are various strategies for gaining access.

Paywalls

A paywall is a means of restricting access to online information content to those who have paid for it.

You may find details of databases and journal articles on the internet, but then find you cannot access them because the publishers have put up a paywall. They may ask you to log in with a username or password, which will only work if a payment has been made, or they may ask for a payment there and then.

The role of libraries and librarians

One of the main roles of the modern library is to pay for subscriptions to online journals and databases so that all the members of that library can get free access. Joining a library can be a considerable support to the practice of EBVM. Librarians and information professionals support EBVM through:

- training in literature searching

- one-to-one support for developing a search strategy

- help with retrieving the full text of journal articles.

See What are the best options for accessing evidence if you are a vet in practice? (Acquire 4.2) for more information.

Institutional subscriptions

Organisations without a library can buy a subscription to journals and databases for members of that organisation to access. The subscription price can vary depending on the number of people who will have access. Institutional subscriptions are used by research centres, companies, and veterinary practices.

Individual subscriptions

Individual veterinarians or researchers can buy a subscription to journals for their own personal use.

Pay-per-view

Journal publishers may offer the opportunity to purchase access to individual articles, on demand as needed. It is convenient and may save money compared to subscriptions, or prove expensive; it depends on what is purchased and how often.

Renting articles

There are services, such as Deep Dyve , that provide, in essence, the ability to rent articles. These are generally 'freemium' payment models, with searching and article abstracts representing the free portion and access to the full articles representing the premium portion.

Open access

There is a strong will among many in the scientific community to make publications open access , with free and unrestricted access online.

Many research councils are now making it obligatory for the publications arising from the research that they fund to be made available open access, and so it is likely that this trend will grow in future years. Some journals are purely open access, but some traditional journals make individual articles available as open access if the author of the article pays a publication fee.

Veterinarians can gain a lot from the open access movement – as it grows, more and more sources of evidence will become freely available to all.

We can all contribute to the open access movement by publishing our research open access whenever possible!

3.1. For those in universities

It’s a huge advantage to have access to a university library, as it will give its members free access to databases and journals.

University and college libraries spend a large proportion of their budget, sometimes literally millions, on such subscriptions to databases and electronic journals (eJournals). Libraries sign licensing agreements with the publishers that mean they can legally only give access to their constituent members.

If you are a member of a university, be sure to use its library for your EBVM.

Visit the library website

You can usually find out which databases and journals you have access to via your library catalogue or website.

Contact your librarians

Librarians have knowledge and expertise and can provide:

- training in literature searching

- one-to-one support for developing a search strategy

- help with retrieving the full text of journal articles.

Make the most of your library membership while you have it

When you leave university, you lose your library membership and access, so make the most of it while you are there.

See if there are any options for retaining library membership

If at any point in your career you undertake a professional development course at a university, find out if this gives you library access – it might, even if you are part time or a distance-learner.

Libraries can sometimes include affiliated members of the university in their membership, so if you are working at a university but will leave, find out if you can be awarded visiting or honorary status that maintains your library access.

Some university libraries offer visitor membership, but this rarely includes access to online resources due to the licence agreements.

3.2. For vets in practice

What are the best options for accessing evidence if you are a vet in practice?

Veterinary practices and individual veterinarians need to investigate practical affordable strategies to access the best available evidence.

In human medicine in the UK, doctors rely on National Health Service (NHS) library services to provide access to much of the evidence they need for EBM. The lack of an equivalent to the NHS in the veterinary community means that there is no national body to pay for access to the databases and peer-reviewed journals that hold some of the most useful scientific evidence, and so alternative routes must be found. This is one of the key challenges for members of the veterinary profession looking to take EBVM forward.

Here is a great article by Jake Orlowitz from Wikipedia that offers advice on getting access, including how to find open access journals and free legal copies of journal articles online: You’re a Researcher Without a Library: What Do You Do?

In summary, some of the key options for veterinarians to consider are listed below.

Database options

Use the free databases to search the evidence

PubMed and PubAg are both free to search, but of course many of the articles they index will still be behind paywalls. But they would be good places to start if you have limited access to veterinary databases. Google Scholar is another free option.

A cheaper alternative to CAB Abstracts

The key database, CAB Abstracts, is costly, and for this reason the publishers, CABI, have created a derivative product that is more affordable for veterinary practices:

- VetMed Resource contains a sub-set of the records in CAB Abstracts selected for their relevance to vets. It is said to have a similar percentage coverage of the veterinary journals to CAB Abstracts. The only loss might be that it does not include some interdisciplinary journals that might be relevant to some veterinary questions (e.g. relating to agriculture and the environment).

Investigate library access

If you are looking to create an evidence synthesis or do a systematic search of the literature, you should consider joining a library that can give you the access you need, or that has librarians or information professionals who can manage the search and retrieval for you.

In the UK, RCVS Knowledge Library & Information Services aims to support veterinarians in their EBVM by providing individuals with access to veterinary databases and journals for a membership fee. The Information Specialists offer a literature search and document supply service, which gives practitioners the opportunity to conduct systematic searches of the veterinary literature.

This may well prove an economical way for vets and vet nurses worldwide to gain access to the key databases and full-text articles. Members acquire access to most veterinary journals, including Veterinary Clinics of North America, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association and Veterinary Surgery. Even if you are not a member, the RCVS Knowledge Library can provide you with copies of articles at a cheaper rate than most pay-per-article options on publisher websites. If the RCVS Knowledge Library cannot provide access to the article you need, it can usually get it from another library.

Use your university libraries access Click to expand

If you are a student, staff, or faculty at a university, your university login can provide the physical and online library resources and services. These include journal and bibliographic database subscriptions and assistance from professional librarians. Depending on the university, adjunct faculty may also qualify for library benefits.

Visitor access to university libraries Click to expand

Many libraries allow those without membership to use the library, whether they are residents of the area, or visiting. For example, in the UK, visitors to the Oxford University Libraries may apply for a reader card for a fee. In the US, land-grant status universities often allow visitors to use the resources in person at no cost.

Check with your public library Click to expand

Ask your public library what bibliographic databases and online journals are provided. Sometimes veterinary journals are included in interdisciplinary packages that the library subscribes to!

Use your public library’s interlibrary loan service Click to expand

For a small fee many public libraries can order many different publications, including journal articles, for you.

Use national libraries Click to expand

Some offer national schemes to help get access to subscription resources. For example, vets resident in Scotland should be able to access some eResources by registering with the National Library of Scotland . Anyone can request a British Library Reader Pass and use materials while at the library in London.

Find a veterinary library Click to expand

The International Directory of Veterinary Medical Libraries is available from the Veterinary Medical Libraries Caucus of the Medical Library Association.

Consider benefits of your professional membership

Most vets and vet nurses have at least one professional membership, and benefits may include journal or database access.

Ask what your membership provides

Be proactive

Tell them EBVM support is important to you

Lobby for additional benefits

Examples of member benefits

- RCVS Knowledge : membership of the library is open to all veterinary professionals. See more information above.

- British Small Animal Veterinary Association : VetMed Resource, BSAVA manuals, formulary

- American Veterinary Medicine Association : journal subscriptions

- British Veterinary Association : journal subscriptions and online resources

- European Society of Veterinary Dermatology : Veterinary Dermatology and more than 20 other journals

Pay for access

Subscribe to key journals or pay-per-view

As a practice or individual, once you have identified the journal titles that publish the best evidence in your field of practice, you could set up an online subscription (which would often enable you to search the backfiles as well as the current issue). Failing that, you could just set a budget to pay-per-view for the articles you need.

4. How do I search for the evidence?

Having identified the best sources of scientific literature that you have access to, you then need to conduct a search for suitable studies to answer your question.

Search strategy

You need to develop a search strategy so that you can be systematic in your searching and find as many of the relevant studies as possible, without missing any.

For those aiming to publish evidence syntheses

Evidence searches should be thorough, objective and reproducible, using a range of sources to identify as many studies as possible (within resource limits), to minimise bias and achieve reliable estimates of effects (Higgins et al., 2019).

For those using evidence, e.g. busy practitioners

A lack of time, funds, expertise, access to technology or resources need not negate an evidence search; we simply need to be as systematic as possible within the practical constraints we have. (Levay and Craven, 2019).

For those wishing to learn how to search the primary literature themselves

Start with a great question!

Consult EBVM Toolkit 2: Finding the Best Available Evidence

This guide was written by RCVS Knowledge Library staff to give a simple overview of best practice methods. It explains how to convert your PICO into a search strategy – take a look to see an example of how to do this. Also read the Ask section of this course.

Move onto searching!

It is worth investing some time in learning how to search bibliographic databases effectively. Understanding key principles of searching can help, but each database works in a slightly different way, so you need to learn how to use each different database.

Teach yourself how to search

Online training tutorials, guides and help pages from the database publishers can be a great source of help and they’re always there, whenever you are working 24/7/365!

Examples of free, online database training guides:

- PubMed for Veterinarians : an online tutorial by librarians at Texas A&M University.

- PubMed online training from the US National Library of Medicine

- Ovid : online training for MEDLINE and Embase

- Scopus : Learn and support, YouTube tutorials

- Web of Science : training and support for Web of Science, EndNote, and Kopernio YouTube tutorials

- CAB Abstracts – Resources for Database Users: schedule of live webinars, recorded webinars, and systematic review tools for CAB Abstracts on OVID and CAB Direct

- VetMed Resource training videos from CABI Publishing

TIP: Don't forget to ask medical and veterinary librarians and information professionals. They are trained in systematic literature searching and can offer advice and support. For example, in the UK, the RCVS Knowledge Library & Information Services can run literature searches for veterinarians.

4.1. A database search strategy

A search strategy ensures that a database search will be systematic and comprehensive.

One of the best ways to learn the fundamentals of database searching is to look at an example of a search strategy and see if you can follow the rationale and logic. Once you can do this, it becomes easier to translate the basic principles to your own searches.

Have a look at the search strategy in the table below and work through it line by line to follow the logic. Some of the terms may be unfamiliar: Boolean operators, subject heading, free text. These will be explained in more detail in the next few pages of the course.

This example is based on a search on CAB Abstracts and can be revised for other databases, which may use different subject headings. You can build a similar search using the ‘Advanced’ search in PubMed or VetMed Resource.

4.2. Search terms

Once you have written your question (see the Ask section), use the PICO or SPICO terms to help you build your search strategy.

Example Scenario

Here is an example using (S)PICO i.e. including species:

In [cats with naturally occurring chronic kidney disease] does [a renal prescription diet compared to normal diet] increase the [survival time] of affected cats?

Step 1:

Make a list of the key concepts needed to build your search.

In this example, the key concepts for the search strategy would be ‘cats’, ‘kidney disease’ and ‘diets’.

Note: The (S)PICO and the Search Strategy are not the same thing!

It is likely you will not search on all your (S)PICO terms. For example, 'Outcome' terms are often excluded from a search because they can be broad terms with many alternatives, meaning key articles may be missed if they are used. Also, outcomes may not be mentioned in the abstract, particularly if the outcome is recovery.

Step 2:

Think of synonyms and alternative terms for each concept. Click the cards below to show examples of these.

Plural terms

Mouse

Rotate

Mice

Rotate

Moose

Rotate

Moose

Rotate

Diseases

Brucellosis

Rotate

Bang’s Disease

Rotate

Hypoadrenocorticism

Rotate

Addison’s Disease

Rotate

Hyperadrenocorticism

Rotate

Cushing’s Disease

Rotate

Paratuberculosis

Rotate

Johne’s Disease

Rotate

Young animals

Dogs

Rotate

Puppies

Rotate

Horses

Rotate

Foals

Rotate

Cats

Rotate

Kittens

Rotate

English and Latin terms

Itch

Rotate

Pruritis

Rotate

Rash

Rotate

Exanthem

Rotate

Alternative spellings for your terms

Colour

Rotate

Color

Rotate

Centre

Rotate

Center

Rotate

Practise

Rotate

Practice

Rotate

Faeces

Rotate

Feces

Rotate

Oesophagus

Rotate

Esophagus

Rotate

Paralyse

Rotate

Paralyze

Rotate

Ageing

Rotate

Aging

Rotate

Grey

Rotate

Gray

Rotate

Moult

Rotate

Molt

Rotate

Abbreviations and acronyms

NSAID

Rotate

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

Rotate

ACL

Rotate

Anterior Cruciate Ligament

Rotate

BCC

Rotate

Bull Cow Calf

Rotate

COPD

Rotate

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Rotate

Step 3:

Be as specific as possible, and where you are interested in a broad topic, e.g. kidney disease, list the more specific topics, e.g. types of kidney disease, that you want to cover.

Table 7: Examples of specific topics related to kidney disease

| Cats | Kidney disease | Diets |

|---|---|---|

|

Feline |

Chronic renal failure |

Kidney diet |

|

Felines |

Chronic renal disease |

Renal diet |

|

Felis |

Chronic renal insufficiency |

|

|

Chronic kidney failure |

||

|

Chronic kidney disease |

Prescription diet |

|

|

Chronic kidney insufficiency |

Therapeutic diet |

Figure 3: Breaking down a topic to maximise search effectiveness

This diagram shows how you might break down a topic (diets in cats with chronic kidney disease) into key concepts (diets, cats, kidney disease) and then use synonyms or related terms for each concept in your search strategy.

For example, under 'diets' you could search for renal diet, kidney diet, prescription diet and therapeutic diet. Under 'kidney disease' you could search for chronic renal failure, chronic renal disease, chronic renal insufficiency, chronic kidney failure, chronic kidney disease and chronic kidney insufficiency. Under 'cats' you could search for cat, feline, felines and felis.

This will maximise retrieval of relevant publications, as authors may use different terms to describe the same concepts.

4.3. Types of search

There are two types of search: free text searching and subject heading searching.

Using a combination of the two can help maximise the chances of retrieving the most relevant evidence.

Free text search

A free text search instructs the database to find exactly what you type in the search box, regardless of the meaning.

radius – results related to the arm bone and results related to the geometric measure

cat – results related to the feline animal and results related to computed axial tomography scans

Free text may seem to be the simplest method but it’s not necessarily the most effective method.

Warning:

- Include plurals

A search for ‘dog’ might not always retrieve results containing the word ‘dogs’. - Include variant spellings

A search on ‘animal behaviour’ (the UK English spelling) might not always retrieve results containing ‘animal behavior’ (the American English spelling). - Beware of context-specific meanings

A search for ‘membrane’ means one thing to a biologist and a different thing to an engineer.

This is particularly important if you’re searching a resource which isn’t subject specific, such as Google Scholar.

Subject heading search

If the database has subject headings or thesaurus terms you should take full advantage of this. It will retrieve results the database publisher has grouped together as being related. The results may contain related terms, which you may not have thought of, and this should improve the results of your search.

Subject headings are specific to each database and are variably called:

- MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) in PubMed and MEDLINE

- CAB thesaurus descriptors in CAB Abstracts

One of the most common mistakes in veterinary searches, is that the species search terms are incomplete. The search often contains a keyword term for the species, however, it does not also include the subject heading. This can result in a large number of relevant papers being missed. The critical point is that a variety of terms could accurately describe a species without describing it completely.

Combine free text and subject heading searches

It is recommended practice to run both a free text search and a subject heading search for each of your key concepts and then to combine the two searches with the Boolean operator ‘OR’. This will maximise the chances of you retrieving all the most relevant evidence for that concept because:

New records in PubMed and MEDLINE don’t necessarily have subject headings added immediately.

It can take months for some records to be completed; you can only retrieve very recent articles with free text terms.

Using subject headings relies on the database producers adding the subject headings correctly.

Sometimes the databases can omit relevant subject headings.

Return to the example search strategy to see how this can be done.

4.4. Boolean operators

Boolean operators instruct the database or search engine on how to combine your search terms and how to search for the information requested.

The Boolean operators are AND, OR and NOT.

These search conventions are used by most search engines and search tools.

You should become familiar with using them as they can make a big difference to the relevance and number of results you get.

Table 8: Boolean operators

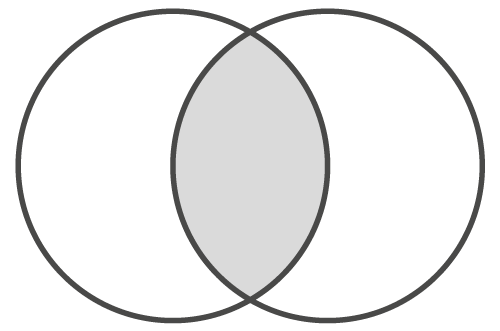

cats AND dogs  |

AND | 'AND' retrieves only the records containing all the combined terms: this example has retrieved records about both cats and dogs. |

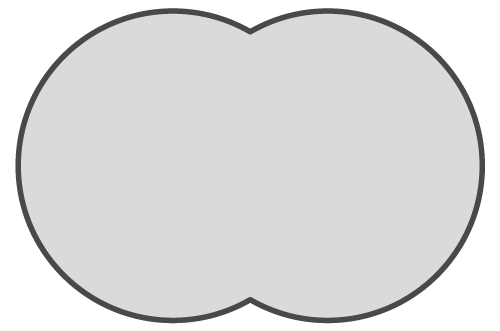

cats OR dogs  |

OR | 'OR' retrieves only the records containing any of the combined terms: this example has retrieved records about either cats or dogs, or both. |

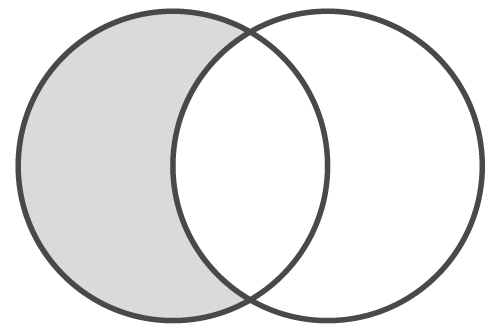

cats NOT dogs  |

NOT | ‘NOT’ retrieves records containing one term but excludes records containing an unwanted term: this example has retrieved records about cats but has excluded everything about dogs. WARNING: Use ‘NOT’ with caution, as it can exclude records which may be useful. For example, if a paper is about cats, but mentions dogs (e.g. “dogs were present in the household”) then the use of ‘NOT’ will lose those papers. |

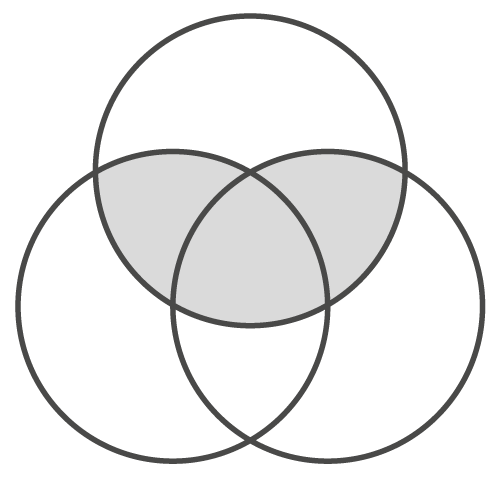

Kidney disease AND (cats OR dogs)  |

AND & OR | Use more than one Boolean operator to make more complex refinements: this example has retrieved records about kidney disease and either cats or dogs. |

Nesting

Most databases are programmed to give ‘AND’ precedence over ‘OR’ in a search, but you can override this by putting terms in parentheses. This enables you to specify the order in which the terms should be searched. Terms within parentheses will be found first, and then combined with terms outside them. This technique, called nesting, is commonly applied when you have multiple search terms for the same concept.

Here is an example:

(cats OR dogs OR felines OR canines) AND Kidney disease

Different databases follow different rules

...Check the help files for the database and platform you are searching!

PubMed performs Boolean operations from left to right unless brackets are used.

PubMed inserts AND between terms if you do not add your own Boolean operator.

4.5. Search tips

When searching bibliographic databases, it’s important to remember that the database will only search for what you tell it to search for.

If you’re looking for resources on different types of livestock and use the search term ‘livestock’, the database won’t know that you’re interested in searching for cattle, sheep, goats, and poultry, unless you use those as search terms.

If you’re looking for resources on different types of livestock and use the search term ‘livestock’, the database won’t know that you’re interested in searching for cattle, sheep, goats, and poultry, unless you use those as search terms.

Be specific in your searches.

It is good practice to search for each concept separately. Having done this and perused the results allows verification that the terms retrieve relevant results for each concept. Then combine the individual concepts into a single result representing your (S)PICO . In most databases this is accomplished by using the Advanced search function or the Search History. These allow you to see the previous searches and results and to combine, recombine and edit them.

This has the advantage of enabling you to see the number of search results each concept gets.

That might help you to refine your search terms!

Boolean operators allow you to build your search up term by term...

…and then combine these terms in a variety of different ways, depending on how useful the results are.

Useful features you can use when searching

Truncation – This usually uses the symbol asterisk * at the end of a search term. This allows you to search for all possible endings, e.g. therap* will find therapy, therapies, therapeutic, etc.; diet* will find diet, diets, dietary, etc.

Proximity searching using ADJn, NEAR/n, NEXT – These work best when searching closely related words that you would expect in a paragraph, e.g. therap* NEAR diet*

Wildcards – This usually uses the question mark symbol ? to replace a letter within a word, e.g. an?esthesia will retrieve anaesthesia and anesthesia.

The symbols and functions for wildcards and truncation vary between different databases and search tools.

Check the help pages for each database to see what they support and use before starting your search.

For instance, Google doesn’t support truncation with an asterisk; instead it truncates automatically using stemming algorithms. However, asterisks can be used in Google as wildcards.

You can use these features to ensure that searches are comprehensive.

For example, when searching for information on cattle, a comprehensive search could be:

(cow OR cows OR cattle OR calf OR calves OR bovin* OR bovid* OR steer OR steers OR freemartin)

4.6. Limits and filters

You can apply limits and filters to ensure that you have fewer irrelevant results to look through. Most databases offer the ability to refine your search results using different parameters:

Publication date Click to expand

The most commonly used limit is publication date – you can limit your search results to articles published in a particular year range. However, it is important to remember that older papers may still be valid and relevant.

Geographical area Click to expand

Some databases allow you to limit by geographical area (for databases which use subject headings, there are usually geographical subject headings which you may wish to use). However, bear in mind that you may exclude some relevant articles when you limit by geographical area.

Language Click to expand

Most databases allow you to limit your results to publications in specified languages. In systematic reviews it would not be acceptable to apply language limits, as here you would need to report all the publications retrieved regardless of the language, so that others who might speak the languages could potentially appraise the evidence available.

Publication type Click to expand

In some databases you can also restrict to certain publication types or study types such as journal article, conference paper, randomised controlled trial, meta-analysis or review, though this is not always reliable.

Search filters Click to expand

Some databases allow you to apply search filters (also called methodology filters) to your search. Search filters are pre-created search strategies which can be used to retrieve particular types of study, such as systematic reviews or meta-analyses. You can use the help pages of the different databases to find out which filters are available in that database. For example, the publishers of CAB Abstracts have produced a search filter to retrieve systematic reviews or meta-analyses in CAB Abstracts and Global Health called CABI filters (pdf).

4.7. Refining your search

Searching databases is an iterative process.

As you review your results, you may decide to refine your search strategy to include, exclude or amend some search terms, limits and/or filters. This is a normal and necessary part of the literature searching process.

Here's some advice to help you address the most common search problems.

Firstly, if you already know of key papers in your field, check that they have been found by your search. If they have not, consider revising your search strategy until they are found.

If you have too many hits: narrow your search

If a carefully conducted search yields lots of results, this suggests your area of interest is complex and researched widely.

Be specific Click to expand

Use search terms that are as precise as possible.

Boolean operators Click to expand

Use the powerful ‘AND’ operator to refine your search by adding extra search topics.

Limits Click to expand

Reduce the parameters of your search by selecting publication year, language, publication type, etc. There is a full range of limits, but use some with caution, for example, restricting your search to articles in English is an arbitrary measure, probably excluding excellent research.

Focus Click to expand

Some databases have a 'major heading' option for subject heading terms, restricting the search to articles with your term as a main subject. Again, use this with caution as you may miss some excellent articles.

Subheadings Click to expand

Some databases have subheadings, e.g. drug therapy, surgery and aetiology in MEDLINE. These allow you to qualify subject headings to limit them to specified facets of research. Be cautious with subheadings – they are not always consistently applied, and you may miss relevant articles.

Search filters/methodology filters Click to expand

Apply ‘ready-made’ search filters to find the right data. Some databases have them as Limits, or you can use methodological filters for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, etc. Validated search filters, e.g. for different study types such as RCTs and systematic reviews, are available on the InterTASC website .

If you have too many irrelevant hits

Subject headings Click to expand

You will retrieve a higher proportion of relevant articles if you search with subject headings rather than with free text alternatives. But this does risk missing new articles that have not yet been given subject headings, e.g. in MEDLINE and PubMed.

Thesaurus display Click to expand

Use the subject tree/index to find more precise subject headings.

Avoid using the Boolean operator ‘NOT’ Click to expand

See above.

Limits Click to expand

It can mean you miss relevant results.

If you would like more hits: broaden your search

Check your spelling Click to expand

It may seem obvious, but incorrect spelling, particularly in free text searching, will reduce the number of results. It’s easy to spell cattle with three 't's, for example! Beware of alternative spellings during textword/keyword searches (e.g. behaviour/behavior; immunisation/immunization).

Explode Click to expand

Subject headings are hierarchical; a broad term has narrower terms under it. This may seem an odd term, but choosing a search heading and searching it and all the narrower terms is called exploding the subject heading. Subject headings are often described with the visualisation of a tree with branches. The broad terms are the large branches and the narrower terms are smaller branches from it. An example of this is PubMed’s MeSH subject headings, the MeSH Tree.

Avoid subheadings Click to expand

Select ‘All subheadings’ when you are presented with the option, because the subheading system is not entirely reliable.

Synonyms Click to expand

Most database content is international, so if your search terms do not map to any appropriate subject headings, think of North American or other equivalents.

Lateral searching Click to expand

Look at the subject headings tagged onto a relevant article. Use those terms to expand the scope of your search.

Free text searching Click to expand

Make sure you are using free text (or keyword) searches as well as subject heading searches, as some concepts will not be captured by subject headings, but will appear in the title and abstracts of publications.

Related terms Click to expand

Use the truncation symbol (the symbol can vary between databases, but the most common one is *) in your textword/keyword search to retrieve words with a common root. ‘Tubercul*’ will bring up tuberculosis, tuberculin, tubercule, etc.

Search other databases too Click to expand

No database is complete. In addition to CAB Abstracts and MEDLINE or PubMed, try the Biosis Citation Index, Web of Science, etc.

Avoid limits Click to expand

Especially ones that don’t influence the quality or relevance of search results (for example, ‘abstract only’).

4.8. Citation searching

Citation searching is a powerful method for finding publications relating to your field of research, which might not be found using conventional search strategies.

This type of search is often done in addition to standard database searching, to increase the recall of all the relevant literature.

Find one relevant publication and you can locate others by ‘time travelling’:

Go back in time

Explore the list of references at the end of the publication to explore the literature that informed the author(s).

Go forward in time

Explore newer publications that ‘cite’ the publication (see How to do citation searches below).

The metaphor 'citation pearl growing' describes citation searching, as it’s like seeing a single grain of sand (your one useful publication) grow into a beautiful pearl (a list of many useful references).

Warning:

This method should not be used in isolation when searching for evidence as large amounts of information could be missed.

Where to do citation searches

Certain subscription databases have a citation index created from the lists of references that appear at the end of journal articles. This means you can also find articles that cite that journal article, as well as the articles which that article references.- Web of Science from Thomson Reuters – includes the three original citation indexes, including the Science Citation Index)

- Scopus (from Elsevier – the main competitor to Web of Science)

A freely available option is:

Google Scholar offers citation information in the search results.

The results of Google Scholar may not tally with those of the formal, bibliographic databases, since they have different coverage: Google Scholar citations are found online so may include pre-prints, conferences, non-indexed publications and non-reviewed websites; by contrast, Web of Science and Scopus citations are curated from a specific list of publications.

How to do citation searches

Step 1. Choose a key publication that is highly relevant to your search

A brand-new publication usually doesn’t work as well because researchers need time to find the publication you are searching for citations of, read it, write something of their own that includes your article in the references, and publish their piece.

Step 2. In one of the tools listed in 'Where to do citation searches', conduct a search for your article (for example, an author/title search or use 'Cited Reference Search').

Step 3. The citations relating to your article will be accessible via links called variably 'Citation network', 'Cited By', or 'Related Articles'.

Advantages of citation searching Click to expand

-

You can follow a line of scholarly communication on a given topic over time.

-

You can find publications that were not found via standard database searches.

-

You are not constrained by the vocabulary of a search strategy or bibliographic record. You may also find articles from unexpected disciplines.

-

You can go backward and forward from a ‘seed’ reference.

-

You can gauge the ‘impact’ of a publication by looking at the citation count; articles that are frequently cited have had greater impact or influence in the scientific community (though of course there will be exceptions to this, for example, papers which are disputed can be heavily cited, so you still need to appraise the paper yourself).

5. How do I manage my search results?

To minimise bias, the process of scanning the results of a database search should include pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Scanning your results generally goes as follows:

- Title sift – scanning all the titles your search finds to see if they are relevant to your question (and discard those that are not).

- Abstract sift – reading through the abstracts from your title sift to see if they are relevant to your question.

- Full-text sift – reading through the full manuscripts from your abstract sift to see if they are relevant to your question.

- Studies included in your review.

Following this process, you can identify the studies relevant to your (S)PICO to include in your review.

TIP: Remember to save your search strategy as you go along, so that you can re-run the search at a future point if necessary.

In the next section Appraise you will find out more about how to assess the relevance of your evidence, including the levels of evidence and identifying the best study designs to help to answer your (S)PICO

5.1. Additional reading: Not enough evidence?

It is not unusual for a veterinary (S)PICO search to retrieve no evidence, but there are a number of constructive things you can do if this happens.

If your database searching finds zero publications, consider why this might be and what you can do next.

There are four main reasons why you might get zero hits.

1. The evidence doesn’t exist

The body of veterinary literature is relatively small compared with that for human medicine, so it may be that there is just no published evidence out there that answers your question.

If you find that there is no evidence, report and publish this.

- It helps identify gaps in the evidence base

- It helps focus new research funding and effort where it’s needed

- It prevents duplicated effort (i.e. saves someone else wasting time repeating the search)

You will find many examples of evidence syntheses that report zero hits – this is not a sign of failure!

For example:

While it may be tempting to refine our question in light of zero hits, or abandon publishing an evidence summary, we should guard against bias and openly report areas where evidence is lacking.

Just because there is no published evidence for treatments does not mean they do not work. When literature searches reveal gaps in available evidence this can be seen as an opportunity to identify new areas for publishing research, but can also be a reminder that formally published studies are only one part of EBVM, with the preferences of patients/owners and the knowledge and experience of vets also key factors in decision-making.

2. The evidence exists, but can’t be found via bibliographic databases

Remember, the bibliographic databases generally only list formal publications, and will not always retrieve grey literature or evidence that has not been published.

For vets this is a particular issue, as much evidence may be tucked away in practice clinical records, rather than scientific publications.

Vets need to be open to using other sources/methods for finding published evidence:

- Grey literature/unpublished data/online sources

- Case records we may have access to locally

- Using social media/social networks to locate others who know of relevant evidence

3. The evidence does exist in the databases, but we’re not finding it

It might be that our search strategy is not effective for retrieving evidence from the databases. Things to consider:

- Get your search strategy checked by a colleague or librarian, to see if it has errors in it or if it can be improved.

- Avoid 'over-specification' where your query is too narrow and so yields few or no results. Consider dropping an element of your (S)PICO from the database search:

- SPECIES – do you really need to include this in your search?

- PROBLEM – are there broader terms you could use?

- INTERVENTION – there won’t always be studies that directly compare your intervention with your comparison, so try searching on just one of them

- OUTCOME – rarely included in veterinary searches, as the outcome terms are often very broad, with many synonyms, so can cause you to miss relevant results.

- Try to improve your database search skills with training.

4. The evidence exists but you can’t get access to it

Refer to the earlier advice on accessing evidence.

5.2. Sharing a search for publication

Publishing and sharing our evidence syntheses can benefit the whole veterinary community.

If you intend to publish your search it is good practice to report the search strategies so that they are transparent and reproducible.

Reporting your search in a standard way enables the search to be replicated in the future, to identify any new evidence published since the last search was run. It also demonstrates the quality of the search strategy and allows others to assess this – they will want to have confidence that the search captured the most relevant literature.

As a minimum, the following should be reported:

The search strategy

- The names of the databases (including the platform and database coverage dates)

- The search strategies (for example, the full search terms used, with an explanation of any decisions made about these if not self-explanatory, plus the way the terms were combined with Boolean operators)

- Any limits or filters applied to the search (for example, date, language)

- The date on which the search was conducted

- Names of any other sources searched/details of any supplementary searching

The search outcome

- The number of publications that were found in the searches and how many were included in the synthesis

- The inclusion and exclusion criteria used to screen results (for example, duplicates, languages, dates, types of study)

If you plan to publish an evidence synthesis, then the target publisher may have reporting standards that you need to follow. For examples, see:

Guidance on compiling a Knowledge Summary from RCVS Knowledge, which includes a Knowledge Summary Template with a requirement for reporting the Search Strategy and the Search Outcome.

Reporting guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

It is important to follow the guidelines for reporting studies, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Comprehensive guidelines for transparent and comprehensive reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, including a flowchart, are provided on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) website.

SYREAF provides resources related to systematic reviews for animals and food.

Meridian gathers together the reporting guidelines for studies that involve animals.

5.3. Reference management tools

You will find references which you may want to use later or plan to cite.

Reference management tools, or bibliographic management tools, allow you to store and organise your references.

There are several reference management tools available. The University of Edinburgh has produced a comparison table (pdf), which gives information on some of the reference management tools you may wish to consider.

Free

- Zotero – open source

- Mendeley – owned by Elsevier

- EndNote Online – owned by Clarivate Analytics

You can create collections of references on different topics, different conditions, different treatment outcomes and so on, and you can add your own notes to each bibliographic record. As these tools are electronic, they can be searched easily, allowing you to retrieve your key references on a topic quickly.

Many reference management tools allow you to add attachments to the records. For example, you may wish to add your own clinical images, web pages, PDFs or links to full-text articles. You can manually add records from a bibliographic database to reference management tools, but it’s more common to electronically export a set of records into whichever reference management tool you’re using. Most databases support this and have an ‘export’ option.

When you’re exporting records from a bibliographic database to a reference management tool, it’s a good idea to export the whole record. You can always delete some of the fields later, but you may find that you want to retain things, such as the subject headings and the abstract, as these include information which you can search later.

Most reference management tools have plug-ins which work with Microsoft Word and other word processing packages, allowing you to embed your references into a document. You can also re-order and change referencing styles for references in documents, either as you write or after you have completed a document. Reference management tools usually support a wide range of referencing styles, and many list them by journal title as well as by citation style.

Most web-based reference management tools allow you to create groups of records and share them with other people, so if you are working on a clinical project, you can easily share references with colleagues.

7. Summary

Learning outcomes

You should now be more familiar with how to:

- identify the best sources of veterinary evidence

- establish which sources you have access to

- search for evidence

- manage your search results.

Now that you have the evidence you need to use it to answer your clinical question.

See recommended reading on the next page

8. References

8. References

Recommended reading

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D. and Sutton, A. (2012) Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London: Sage

De Brun, C. and Pearce-Smith, N. (2014) Searching skills toolkit: finding the evidence. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell

EBVM Toolkit 2: finding the best available evidence [RCVS Knowledge] [online] Available from: http://knowledge.rcvs.org.uk/document-library/ebvm-toolkit-2-finding-the-best-available-evidence/ [Accessed 31 July 2020]

Greenhalgh, T. (2019) How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine and healthcare. 6th ed. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell

Levay, P. and Craven, J. (eds.) (2019) Systematic searching. Practical ideas for improving results. London: Facet Publishing

Other useful references

Brodbelt, D. (2014) Practice data: building the evidence base: six different presenters provide a fascinating insight into the strengths and limitations of data from practic e. In: Proceedings of the 1st International EBVM Network Conference, 23–24 October 2014, Windsor, UK. London: RCVS Knowledge

Doig, G. S. (2003) Evidence-based veterinary medicine: what it is, what it isn’t and how to do it. Australian Veterinary Journal, 81 (7), pp. 412–415

Fletcher, D.J. et al. (2012) RECOVER evidence and knowledge gap analysis on veterinary CPR. Part 7: clinical guidelines. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care, 22 (s1) S102-S131. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-4431.2012.00757.x

Gibbons, P. M. and Mayer, J. (2009) Evidence in exotic animal practice: a “how-to guide”. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, 18 (3), pp. 174–180

Glanville, J. et al. (2015) Technical manual for performing electronic literature searches in food and feed safety. EFSA

Grindlay, D. J. C., Brennan, M. L. and Dean, R. S. (2012) Searching the veterinary literature: a comparison of the coverage of veterinary journals by nine bibliographic databases. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 39 (4), pp. 404–412

Higgins, J.P.T et al. (eds.) (2019) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Ver. 6.0. Available from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current [Accessed 31 July 2020]

Institute of Medicine (USA) Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research; Eden, J. et al. (eds.) (2011) Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews. Washington: The National Academies Press.

Kastelic, J. P. (2006) Critical evaluation of scientific articles and other sources of information: an introduction to evidence-based veterinary medicine. Theriogenology, 66 (3), pp. 534–542

Knottenbelt, C.M. (2018) Do Palliative Steroids Prolong Survival in Dogs With Multicentric Lymphoma? Veterinary Evidence, 3 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.18849/VE.V3I1.96

Moher, D. et al. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Murphy, S.A. (2007) Searching for veterinary evidence: strategies and resources for locating clinical research. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 37 (3), pp. 433–445

Nolen-Walston, R., Paxson, J. and Ramey, D.W. (2007) Evidence-based gastrointestinal medicine in horses: it’s not about your gut instincts. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 23 (2), pp. 243–266

Olivry, T. et al. (2015) Treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: 2015 updated guidelines from the International Committee on Allergic Diseases of Animals (ICADA). BMC Veterinary Research, 11 No 210. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-015-0514-6

Orlowitz, J. (2017) You're a researcher without a library: what do you do? A Wikipedia Librarian [online] 15 November 2017. Available from: https://medium.com/a-wikipedia-librarian/youre-a-researcher-without-a-library-what-do-you-do-6811a30373cd [Accessed 31 July 2020]

Place, E. and Brown, F. (2016) Literature searching for evidence-based veterinary medicine: coping with zero hits. Veterinary Evidence, 1 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.18849/VE.V1I4.77

Practice Guidelines [AGREE] [online] Available from: https://www.agreetrust.org/practice-guidelines/ [Accessed

31 July 2020]

Whiting, P. et al (2016) ROBIS: Tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews. [online] Available from: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/population-health-sciences/projects/robis/ [Accessed 31 July 2020]

Youngen, G. K. (2011) Multidisciplinary journal usage in veterinary medicine: identifying the complementary core. Science & Technology Libraries, 30 (2), pp. 194–201