ABCs of EBVM

| Site: | Learn: free, high quality, CPD for the veterinary profession |

| Course: | EBVM Learning |

| Book: | ABCs of EBVM |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 15 February 2026, 2:57 AM |

1. Introduction

A new way to think

By the end of this section you will be able to:

- explain the concept of EBVM

- construct a generalised example of the EBVM cycle

- describe the relevance, importance and challenges of EBVM to veterinary practice.

2. What is EBVM?

At its core, evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM) is a structured and explicit method that helps us make decisions, in clinical practice as well as other areas where veterinarians might work.

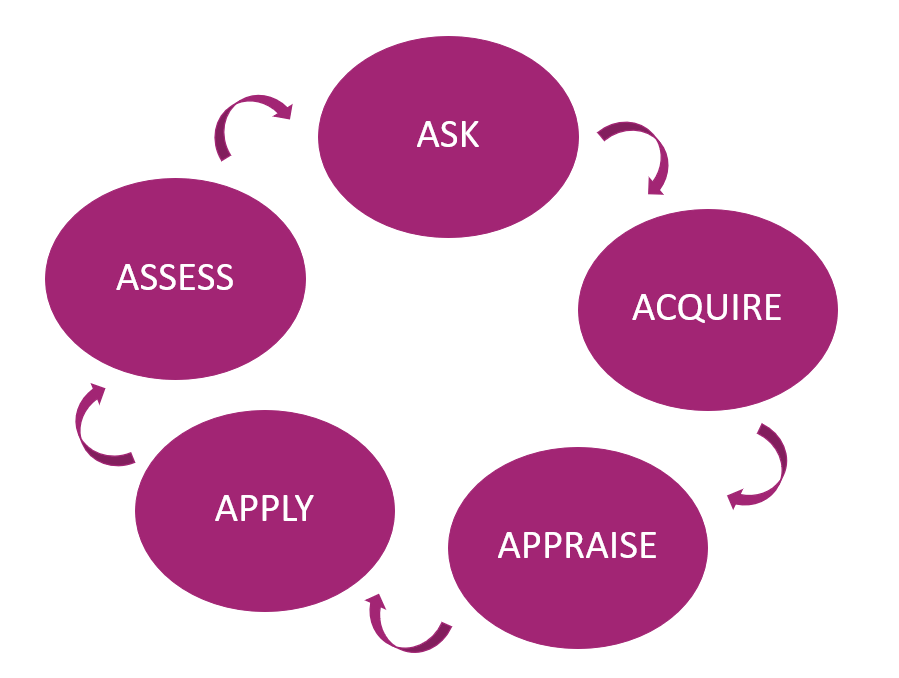

EBVM has been explained as five main steps which form a cycle. The cycle takes its principles from human evidence-based medicine (Heneghan and Badenhoch, 2006) and has been used to produce this course.

Figure 1: EBVM Cycle - The Five Steps

As you progress through this course you will learn about each of the five steps in more detail:

- Ask – defining an answerable clinical question that is of interest

- Acquire – finding out if evidence exists to answer the question and acquiring that evidence

- Appraise – assessing the quality of the relevant evidence found

- Apply – implementing the evidence into clinical practice where appropriate

- Assess– evaluating the impact of the implementation and changes in clinical practice

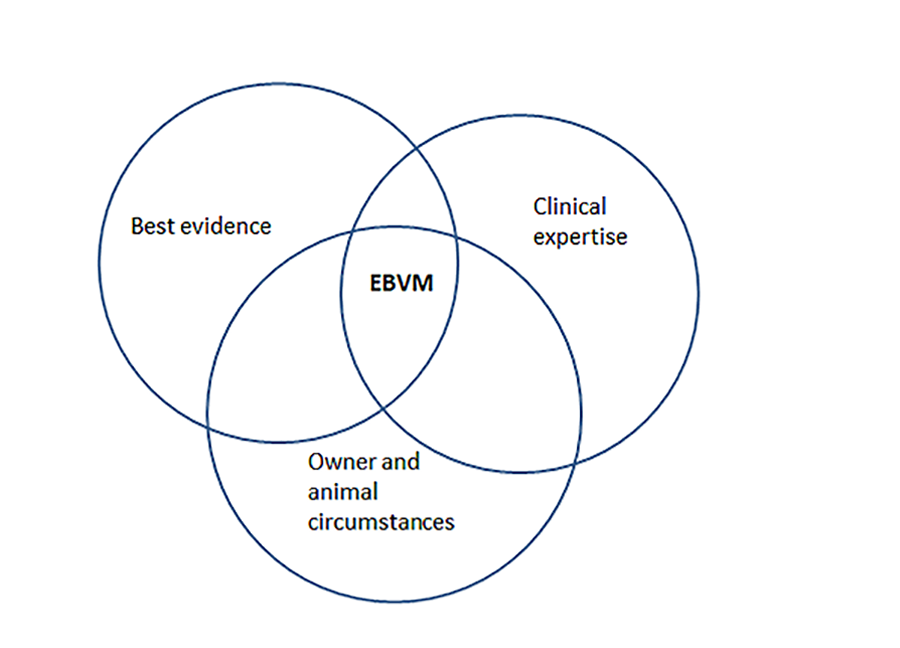

Where evidence does exist to answer our clinical question, we move through the stages of the EBVM cycle, enabling us to construct our own evidence-based decisions. This process incorporates more than just finding the “best” available evidence:

Evidence-based veterinary medicine is the use of the best relevant evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise to make the best possible decision about a veterinary patient. The circumstances of each patient, and the circumstances and values of the owner/carer, must also be considered when making an evidence-based decision (Centre for Evidence-Based Veterinary Medicine, CEVM ).

Figure 2: Decision-making in EBVM

Where evidence does not exist for our clinical question, we identify gaps in the evidence base. This is referred to as ‘zero evidence’ and will be explored in more detail throughout the course.

Many of the terms used in defining EBVM are included for a specific reason but may also raise questions. For instance:

- What is meant by ‘best’ available evidence?

- How do we balance our patient’s circumstances with our owner’s circumstances?

- What importance do we place on our own clinical expertise as compared to what is available in the literature?

- How do we deal with ‘zero evidence’?

We will seek to answer these questions as we proceed through this course – and perhaps come up with a few more!

In this introductory section, we will discover the history of evidence-based medicine (EBM) and the subsequent development of EBVM. We will guide you on your EBVM journey, exploring the clinical applications of EBVM and how to address the challenges you may face.

3. History of EBVM

A tale of old – How Dr James Lind cured scurvy

In the 18th century, sailors died from scurvy on a regular basis. In 1747, on Her Majesty’s Ship the Salisbury, young men under the care of Dr James Lind were dying, despite him following the current treatment recommendations for scurvy. At the time, the Royal College of Physicians recommended sulphuric acid, and the Admiralty recommended vinegar treatments. Dr Lind noted that the recommendations were all written by ‘experts’ who had never been on a long sea voyage.

Dr Lind reviewed the current evidence and ran his own treatment trial to see if he could find a treatment for scurvy. His trial compared the success of a concoction of sulphuric acid, vinegar, nutmeg, cider and seawater to a diet of two oranges and one lemon in different groups of sailors in similar stages of disease, who were otherwise sharing the same basic diet.

The sailors receiving the citrus fruit clearly improved more quickly than those ingesting the tasty sulphuric acid concoction, and Dr Lind had some evidence for a superior treatment. Following this clinical trial, the Admiralty made lemon juice compulsory for sailors, and deaths due to scurvy declined precipitously.

Dr Lind’s study is an excellent early example of the practice of EBM. As a clinician, Dr Lind posed the right, pertinent question about the disease, reviewed the relevant current evidence (literature), recognised the limitations of that evidence, and then executed a simple clinical trial, which led to a change in the way he treated his patients. Dr Lind also passed on his new knowledge by telling the Admiralty and the Royal College of Physicians, who then instituted change, saving many lives at sea.

Over the last few decades, EBM has significantly impacted and, in many areas, improved patient care. There are now many human healthcare initiatives in place to assist evidence-based decision-making:

Challenges remain, highlighted by the British Medical Journal’s publication of the EBM manifesto describing the steps required to develop more trustworthy evidence (Heneghan et al., 2017)

4. The development of EBVM

In this section, we will look at similarities and differences between evidence-based medicine and evidence-based veterinary medicine, and some examples of key evidence-based veterinary medicine initiatives.

4.1. How does EBVM compare to EBM?

EBVM has drawn upon expertise in the medical field, where applying the principles in practice has become widely accepted. For example, in the UK the NICE guidelines provide human healthcare professionals with guidance and advice on the evidence across broad health and social care topics.

Human healthcare professionals’ and veterinarians’ practices are in many ways similar, but significant differences between EBM and EBVM exist, including:

- patient–(owner)–clinician relationship

- availability and quality of scientific literature

- funding and insurance models

- expectations of end-of-life care.

These differences affect how we approach evidence-based practice in the veterinary context and will be explored throughout the course.

A question to ponder:

How often do I use evidence to aid my own clinical decision-making in veterinary practice?

4.2. EBVM initiatives

The principles of EBM are now commonplace in human healthcare, but how has using an evidence base been approached in veterinary practice?

Awareness and use of EBVM is constantly increasing, with the fundamentals of EBVM being taught to undergraduates in vet schools internationally with growing support from key professional bodies such as the British Veterinary Association (BVA) and the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). The quantity of evidence is likely to grow in each of the various specialist areas of the profession.

There are a number of groups taking the lead on EBVM internationally. Find out more about these below.

Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine Association Click to expand

The Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine Association (EBVMA) in North America was founded in 2004 to improve the co-ordination and communication between individuals promoting research, teaching, and clinical application of EBVM to practice (Slater, 2010).

Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine Click to expand

In 2009, the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine (CEVM) at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom was established. This centre has brought and adapted a number of EBM methodologies to the veterinary profession and covers four main areas of research: evidence synthesis, population research, practice-based research and education and information exchange.

RCVS Knowledge Click to expand

RCVS Knowledge is a UK charity with a mission to advance the quality of veterinary care for the benefit of animals, the public, and society. RCVS Knowledge has championed the use of an evidence-based approach to veterinary medicine since 2014, and provides free tools, resources and education to the veterinary professions.

The charity's resources include Veterinary Evidence , a free, open access, peer-reviewed journal that publishes evidence based on questions from veterinary professionals; inFOCUS , a journal watch providing summaries of the latest research with the potential to impact care from over 100 journals; a Library and Information Services ; and a growing suite of quality improvement tools and learning resources .

Other recent initiatives include:

- Evidence-Based Veterinary Medicine Matters , a publication from RCVS Knowledge and Sense About Science supported by 14 UK organisations, including vet schools and policy-making bodies, outlining a commitment to the future of EBVM. The publication makes a strong case for much-needed funding for research to grow the evidence base.

- An CIVME EBVM Toolbox created by a Council on International Veterinary Medical Education project (2019), which provides information for educators who are reviewing or introducing research and/or evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM) in a curriculum.

5. Why is EBVM important?

In this section, we look at the benefits of EBVM in different clinical scenarios and in handling information overload. We also discuss how EBVM can be incorporated into Quality Improvement.

5.1. Clinical applications of EBVM

EBVM can help practitioners in a number of ways.

The ways EBVM can help practitioners include:

- improving confidence in your own clinical decision-making

- dealing with information overload

- developing a structured approach to using reliable evidence-based methods in your practice, for example, practice guidelines

- demonstrating Quality Improvement in practice, which might include the use of EBVM to carry out a clinical audit.

Clinical examples could arise by considering the following:

- a recent journal article that recommends a different diagnostic method or treatment protocol from that which you currently use

- a particularly challenging or unresolved case

- evaluating a new marketing leaflet you have received from a pharmaceutical company

- a need for new practice protocols or guidelines, or to review existing ones

- questions arising from case discussions within the practice

- an area in which you know you would like to develop your skills

- a disease you and your colleagues approach differently in terms of diagnostics or therapy

- a disease process you treat that you feel has unsatisfactory outcomes

- a case report or publication you are keen to work on

- clinical audit activity.

5.2. Information overload

Over recent decades, there have been massive increases in the availability of information, both in the medical and veterinary literature, but also in mainstream media.

For instance, there were 87,000 veterinary papers published in one year (CAB Abstracts 2018) which would equate to reading 238 papers per day – it is not possible to read all the primary literature, or to subscribe to all the relevant journals.

Various strategies for finding and disseminating information have been developed to address this information overload. The availability of evidence summaries (Acquire 3.2) that provide a 'clinical bottom line' is increasing in the veterinary field.

Evidence summaries are produced by asking a clinical question, acquiring and appraising the available evidence and producing a summary of ‘best’ available evidence, often referred to as a ‘clinical bottom line’. Online collections of evidence summaries are freely available through BestBETs for Vets and RCVS Knowledge’s Knowledge Summaries .

RCVS Knowledge's inFocus serves busy practitioners: a simple ‘research news’ update providing concise summaries of important and interesting practice-critical material. Practitioners can access these online or subscribe to a bi-monthly email.

While there is a wealth of information available on the internet, it is important to recognise that the quality, source, and reliability of this information varies, from the evidence summaries mentioned above, to online public discussion forums.

Not all information on the internet is unreliable. Despite the increase in the amount of available literature, there is still scant relevant evidence for many common veterinary conditions, meaning other sources of information need to be considered and appraised. Using the internet for searching evidence will be covered in more detail in the Acquire section.

5.3. How does EBVM apply to Quality Improvement?

Quality Improvement is a systematic approach to reviewing the quality of our practice in order to make changes to ensure continuous improvement. It encompasses a variety of specific techniques and tools, including clinical audit, benchmarking, significant event audit and the creation and implementation of guidelines and checklists.

You might be involved in carrying out a clinical audit in your practice as part of a practice accreditation scheme, such as the RCVS Practice Standards Scheme . More and more practices are signing up to practice accreditation schemes, which provide quality assurance for consumers. The principles of using EBVM in carrying out clinical audit are covered in the Assess section.

Many veterinary practices are following the human healthcare approach and developing their own practice protocols and guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of common conditions. In some cases, these protocols and guidelines will, by necessity, be based on the clinical experience of the practitioners, as this may be the only form of evidence available.

However, as EBVM is incorporated into veterinary practice and more quality scientific evidence becomes available, it is reasonable to expect that such guidelines will incorporate reliable evidence and be developed using the principles of EBVM. This will be covered in the Apply section.

The benefits of using these EBVM principles for Quality Improvement may include greater client and staff satisfaction, better patient outcomes and assist practice management decisions around future business development.

Find out more about Quality Improvement in the veterinary professions .

6. Challenges of EBVM

There are several challenges to EBVM that can be encountered in practice, but by acknowledging these and working together to generate and utilise evidence, integrating EBVM into our daily practice can and will become easier.

6.1. What are the challenges?

Time

Access to journal articles and databases

Even when there is evidence available, frustratingly, it can be difficult to access; journals often require a subscription fee to access research papers. Veterinarians working outside of academic institutions may only have access to a handful of journals through their practice or personal subscriptions and may not have access to databases limiting their ability to acquire evidence.

There are more 'free access' resources available, although the quality of the evidence can vary. One initiative, the RCVS Knowledge Library and Information Services , has seen increasing numbers of practitioners subscribing to its service, which provides access to a range of full-text electronic journals for an annual fee.

Client access to 'evidence'

Clients have access to many of the same resources that veterinary professionals do, but usually lack the clinical expertise to assess whether the advice they find online is sensible. They may have attempted diagnosis, and treatment, before seeking veterinary advice, and the veterinary surgeon now has an important role in educating owners.

A dearth of evidence

Experts agree that there is a lack of high-quality published evidence for veterinary medicine (Dean and Brennan, 2016; Lanyon, 2014), especially in comparison with the larger evidence-base for human medicine and that funding is an issue:

case-based research in the ‘real world’ of veterinary clinics has no funding base to support it"

(Lanyon, 2014)

6.2. What is helping to address the challenges?

A close dialogue with practitioners will help raise awareness of the existing evidence and can inform the direction of future research. There is recognition within the veterinary profession that a greater collaboration and investment in research is required to create a better evidence base from which to inform clinical decision-making.

Collating and analysing existing data

Initiatives to collate data held within clinical record systems (e.g. VetCompass and SAVSNET ) aim to analyse disease trends, interventions and treatments and provide information for academics, clinicians and the public.

Evidence summaries

These are concise summaries of the best available evidence for a clinical question. Evidence summaries save practitioners time, by allowing them to see the 'clinical bottom line' at the click of a button, and facilitate evidence-based clinical decision-making. Examples of open access evidence summaries are:

Perhaps you have a clinical question on which you would like to see a Knowledge Summary written? Submit your clinical query to RCVS Knowledge . Or you might like to have a go at writing your own Knowledge Summary ?

7. How do I start my EBVM journey?

To make the most of this course, it would be useful to take time now to think about clinical scenarios that relate to your practice, and that you can use throughout the course to apply to the concepts we discuss. You will then be guided through the EBVM cycle, and by the end of the course, you may have answered a real problem that you have encountered!

Activity

Think about clinical scenarios that relate to your practice. These could be:

- An area in your clinical practice that you would like to audit

- A recently launched medication/diagnostic test that you are considering using in your cases

- A research paper in a journal that you would like to review.

As you work through each section, try to apply the skills that you are learning to your example.

8. Summary

Learning outcomes

You should now be more familiar with how to:

- explain the concept of EBVM

- construct a generalised example of the EBVM cycle

- describe the relevance, importance and challenges of EBVM to veterinary practice.

9. References

Dean, R. and Brennan, M. (2016) Dearth of evidence for EBVM. Veterinary Record, 179 (10), pp. 258-259

Dean, R. and Heneghan, C. (2019) Do we need an evidence manifesto? Veterinary Record, 185 (2), pp. 58-59

Heneghan, C. and Badenhoch, D. (2006) Evidence-based medicine toolkit. Second ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Heneghan, C. et al. (2017) Evidence based medicine manifesto for better healthcare. BMJ, 357:j2973

Lanyon, L. (2014) Evidence-based veterinary medicine: a clear and present challenge. Veterinary Record, 174 (7), pp. 173-175

RCVS Knowledge and Sense About Science (2019) Evidence-based veterinary medicine matters: our commitment to the future. London: RCVS Knowledge

Slater, M. R. (2010) Epidemiological research and evidence based medicine: how do they fit and for whom. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 97 (3-4), pp. 157-164